One of Europe’s major waterways, the 814km Rhône rises in the Swiss Alps. It’s boosted by multiple tributaries along the way and drops 2,208m over its length before emptying into the Mediterranean near Arles in southern France. By divine design, it flows through the heart of Burgundy and Provence.

Over the millennia the river’s been a strategic factor in many cultures and civilizations. Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans were among the region’s earliest inhabitants. The Rhône served them well, particularly the all-conquering Romans. The waterway was a fortuitous conduit for moving troops and supplies between the Mediterranean and Gaul – and thereafter throughout the continent. It lubricated the Empire’s relentless expansion.

Later, through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, it became a vibrant trade artery – the ‘sauce’ in a melting pot aiding the exchange of products, ideas and knowledge. In the 20th century it became a key power source in France’s massive energy infrastructure. Best of all, for centuries it’s been (and remains) the lifeblood underpinning a world-renowned wine industry.

Later, through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, it became a vibrant trade artery – the ‘sauce’ in a melting pot aiding the exchange of products, ideas and knowledge. In the 20th century it became a key power source in France’s massive energy infrastructure. Best of all, for centuries it’s been (and remains) the lifeblood underpinning a world-renowned wine industry.

Reminders of these ancient cultures are evident in the towns and ports all along the river, many of them now UNESCO heritage sites. They include remarkably well-preserved 2,000-year-old Roman edifices. All in all, a veritable feast of sights, sites, and flavours to savour – and, as we discovered, very accessible by river cruise.

Our voyage began in Lyon and finished in Arles, a downstream, 310km, eight-day cruise aboard the 135m SS Catherine (Sunday–Sunday). The ship also operates upstream. One of many flat-bottomed vessels plying the Rhône, the Catherine is part of the Uniworld fleet. She accommodates 158 passengers and 59 crew – a ratio reflecting the company’s legendary service ethos.

Cruising both overnight and during the day allows guests to absorb the sunsets and passing landscape (best observed on deck with a cocktail in hand), with regular stops for tours. In addition to a full day for exploring Lyon (spectacular), the ship stops at Macon, Tain L’Hermitage, Viviers and Avignon before finishing at Arles.

Each stop offers various excursions designed to meet guests’ different interests and fitness levels. They typically involve walks with knowledgeable guides offering unique insights into the history, architecture, cuisine, and wine of the area.

In Lyon, for example, you have a choice between a tour of the ‘traboules’ (ancient, hidden passages interconnecting parts of the city), a visit to a silk-weaving facility (Lyon’s famous for its silk), or a city cycling tour (using the ship’s bikes).

All are flawless logistical exercises. In keeping with Uniworld’s ‘all-inclusive’ policy, most excursions are free. Some adventures (typically a little further afield, requiring bus transport) charge extra.

In Macon, as an alternative to the walking tour around the nearby medieval town of Beaune (incorporating a fascinating 15th century hospice), some guests opted for the retro motorbike/sidecar visit to a Burgundy vineyard, with wine tasting. There’s a lot of wine-tasting on this cruise…

Further down the river, at Tain L’Hermitage, our group walked among the vines at the illustrious Hermitage Terrace Vineyard – a very special wine tasting in the brilliant sunlight. At Viviers, some guests visited a truffle farm, where these days the delicacy is sniffed out by dogs (traditionally, pigs are used). Others explored a boutique potter’s studio.

At Avignon, some opted for the Papal Palace tour (seven successive Popes lived here for nearly a century in the 1300s because of an internal spat in the Catholic Church. Eventually, things were resolved and the Papacy moved back to Rome). While we learned about Papal infighting, a few wine aficionados visited the nearby, world-renowned Châteauneuf-du-Pape vineyard – with tasting.

My favourite excursion? Kayaking down the Gardon River (a Rhône tributary) and under the 2,000-year-old Pont du Gard. This massive aqueduct is arguably the finest example of Roman engineering in Europe. It was built to convey water to the nearby city of Nîmes – itself famous for inventing a tough, hard-wearing textile used for ship sails (serge de Nîmes). This serge later became the material for today’s ubiquitous ‘denim’ blue jeans.

The aqueduct is one of many Roman remnants along the Rhône. Other striking examples include the terraced theatres in Lyon (still used for concerts and plays) and the amphitheatre in Arles – smaller than Rome’s Colosseum but one the best-preserved such structures in Europe.

Its stunning amphitheatre aside, Arles is a popular destination for art lovers. The city was home to the post-impressionist Dutch painter Vincent Van Gogh for a few very productive years. He raved about the region’s ‘light’ and produced more than 300 works while living here in the late 1800s. They include some of his most famous paintings – The Night Café, Yellow Room, Starry Night Over the River Rhône and L’Arlésienne.

Sadly, Van Gogh suffered bouts of mental illness and famously cut off his left ear before being admitted to a hospital in nearby St Remy, where he died. But he wasn’t the only artist to relish Provence’s unique colours and light. Paul Cézanne was also inspired, as was Paul Gauguin.

Taming the Rhône

Despite its dominant role in fostering southern France’s development, the Rhône has never been easy to navigate. It’s prone to flooding/strong currents in times of heavy rainfall and/or glacial melt and, perversely, very low water during droughts.

Various ‘river-taming’ strategies were implemented over the centuries. The major one arrived in the mid-1900s when numerous hydroelectric power plants were installed, each with an attendant lock enabling marine traffic.

Our ship negotiated 14 locks – and traversing them is a fascinating, very slick process. Among them is the Bollène Lock near Avignon (built 1952). With a fall/rise of 23m, it’s Europe’s second deepest lock. The continent’s lock ‘king’ is the Barragem do Carrapatelo on Portugal’s Douro River (35m fall/rise – one of the planet’s biggest). Most Rhône cruise ships have a beam of precisely 11m – dictated by the locks. They squeeze in with millimetres to spare.

Today, hydro-electric stations provide much of the region’s power, producing 13GWh of electricity annually (around 16% of France’s total hydroelectric production). They’ve been complemented more recently by nuclear power stations on the Rhône’s banks.

Ironically, one of the best strategies to counter the devastating floods was implemented centuries ago at the medieval city of Avignon. It’s entirely walled – one of the few French cities to have preserved its ramparts. While the massive walls repelled invaders during the Middle Ages, they’ve also been very effective in protecting the city from the floods.

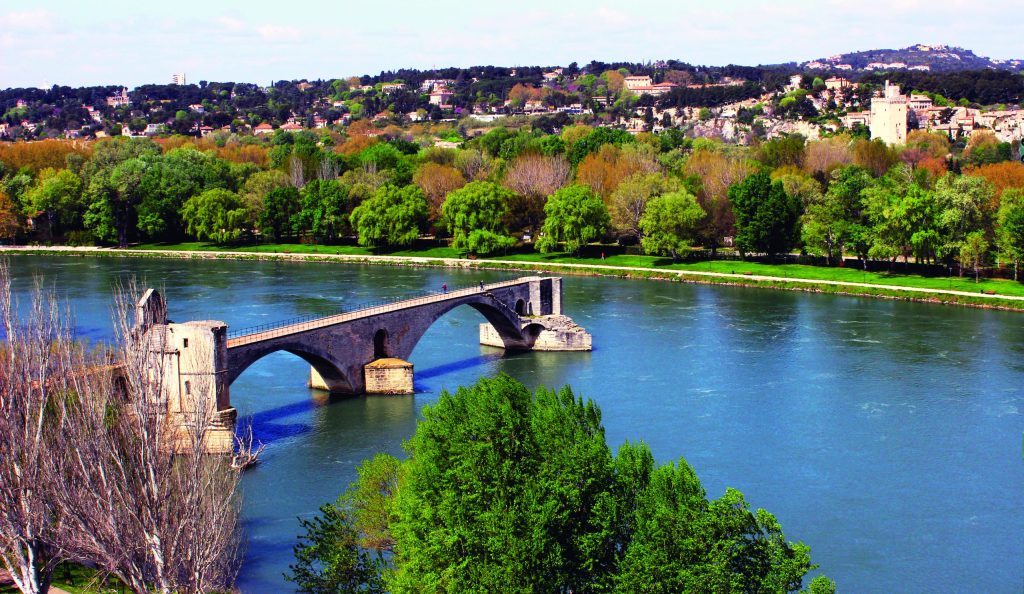

Of course, not all of Avignon survived the floods. Outside the walls is the elegant (and famous) Pont d’Avignon bridge, built across the Rhône in the late 12th century. Destroyed several times by floods/strong currents, the city fathers eventually admitted defeat and in 1680 replaced it with a suspension bridge. Of the original bridge, only four arches remain.

In Vino Veritas

This Latin phrase – ‘in wine there is truth’ – alludes to the likelihood that people will speak more honestly under the influence of wine. Another ‘truth’ is that it’s impossible to cruise the Rhône without tasting exceptional wine.

The region’s relationship with great wine began with the Romans but after the Empire collapsed their clumsy brews were refined by the Catholic Church. Specifically, it seems, by Cistercian monks who had plenty of time to reflect on and experiment with the different soil types and microclimates along the Rhône. All in the quest to serve God with the perfect blend, of course.

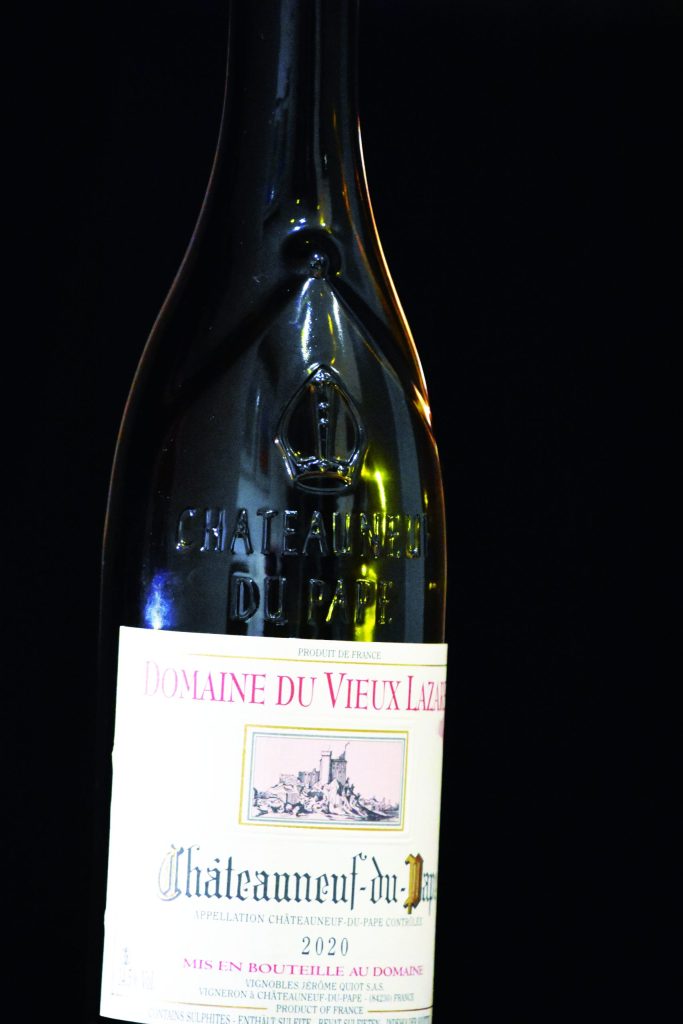

The monks received plenty of encouragement from their CEO. Châteauneuf-du-Pape – one of world’s most famous vineyards – traces its origins to Pope Clement V (in 1309 he became the first of Avignon’s rebel popes). He established a vineyard to develop something more palatable than the local swill. Today the vineyard embosses its wine bottles with a distinctive logo – the Papal mitre.

‘Appellation’ is a word you hear a lot during the cruise.

A wine’s AOC (appellation d’origine contrôlée) refers to France’s system of designating wines (and other produce) according to where they’re created. In broad terms the Rhône Valley’s wines can be divided into Syrah/Viognier in the north and Grenache in the south.

Soil and micro-climates vary considerably over the river’s length, and the subtle influence of these on the wines was underscored by the Catherine’s sommelier. Before dinner each night he delivered a presentation about the local wine he’d chosen to complement the menu – how the soil/climate had shaped the wine – and its notable features. All were premium wines – and magnificent.

That France’s wine industry occupies such a revered position in global rankings is nothing short of miraculous. I was intrigued to learn that Roquemaure – a town on the right bank of the Rhône near Chateauneuf-du-Pape – lives with an infamous reputation.

It was here that the devastating vine pest Phylloxera first attacked French vineyards in the 1860s. The insect was unwittingly introduced from North America and, in what became known as the Great French Wine Blight, eventually decimated around 75% of the country’s vineyards. What a remarkable recovery.

Europe is blessed with an extensive network of rivers and canals. A five-star, luxury cruise along any of them is a wonderfully convenient way (dare I say enjoyably decadent?) for exploring a region, country – or even multiple countries – on a single voyage.

The possibilities are endless, but if you’ve never experienced river cruising and aren’t sure where to begin, a Burgundy/Provence voyage is a trés magnifique option.