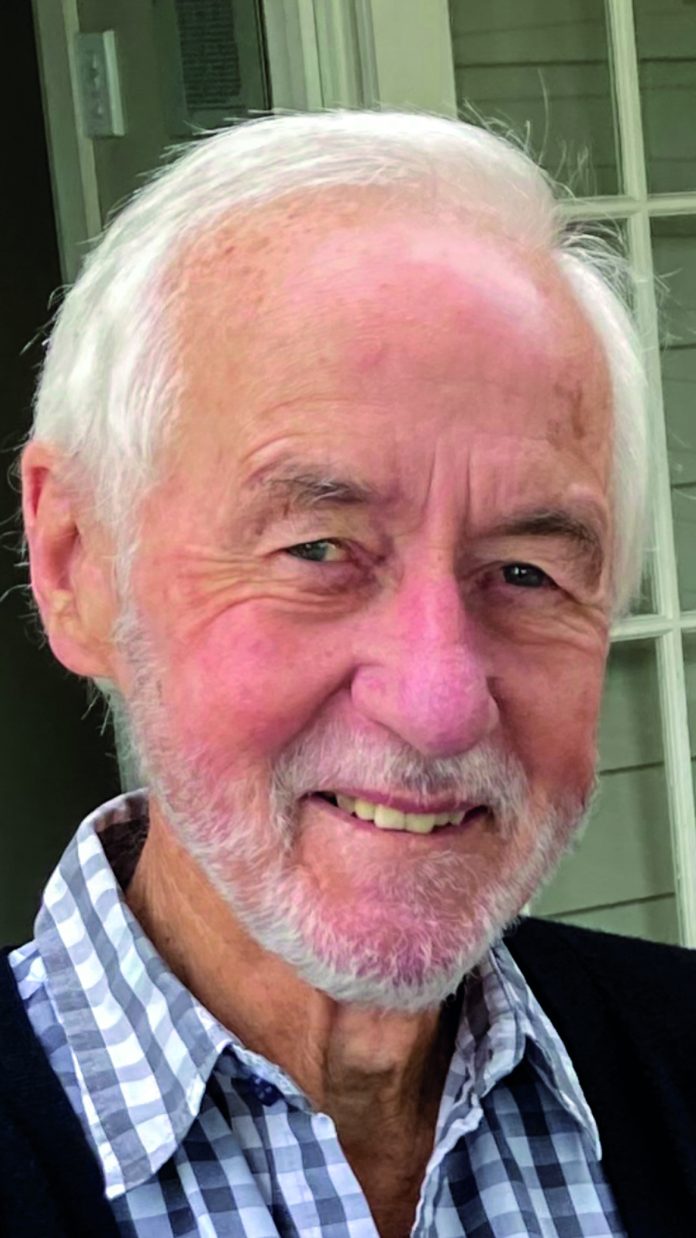

Born in 1946 the youngest of three, Bowler grew up in Auckland and enjoyed an idyllic lifestyle based around the water and boats. His father Ces, a lawyer, and his mother Jean, owned a bach at Lake Rotoma, where a five-year-old Bowler cobbled together a mast, sail and rudder for the elderly family dinghy and tried to sail across the lake. A couple of years later, he learned to sail in the elderly P Class, Charles.

At the time, a group of Whakatane Cherub sailors, which included Micky Orchard, would come to visit the Bowler family, especially Bowler’s two elder sisters.

“The Cherub was a big thing then. I remember these guys talking about centre of effort, and centre of lateral resistance, and stuff like that. It fascinated me.”

Aged 12, Bowler persuaded Ces to buy him a Junior Moth and then, after the family moved to Kohimarama, the competitive P Class Marika Jnr. Bowler was soon racing Marika Jnr competitively twice every weekend. As he improved, Ces bought him a new Terylene sail, then with the 15-year age limit for the Tanner Cup looming, the newer, more competitive P Class Tranquil.

“I had great support from my parents, neither of whom was a sailor.”

Bowler’s main competition was the late Mark Paterson, who would later dominate the Cherub class for decades. However, Bowler beat Paterson in the 1962 Tauranga Cup and, in his final P Class outing, won the Auckland Anniversary Regatta’s P Class event.

Now too old for the P, Bowler built the OK dinghy Neiuffe, and while he won some local races, he always knew he was too light for the OK in more than 15 knots.

Meantime, Cherub forward hand Don McGlashan had married Bowler’s elder sister Katherine. Bowler and McGlashan teamed up to build the Cherub Mecca, a tweaked John Spencer VII design. It took the pair two seasons to gel; however, by 1968 when they sold Mecca, they’d won two North Shore, two Auckland, and two National Cherub regattas.

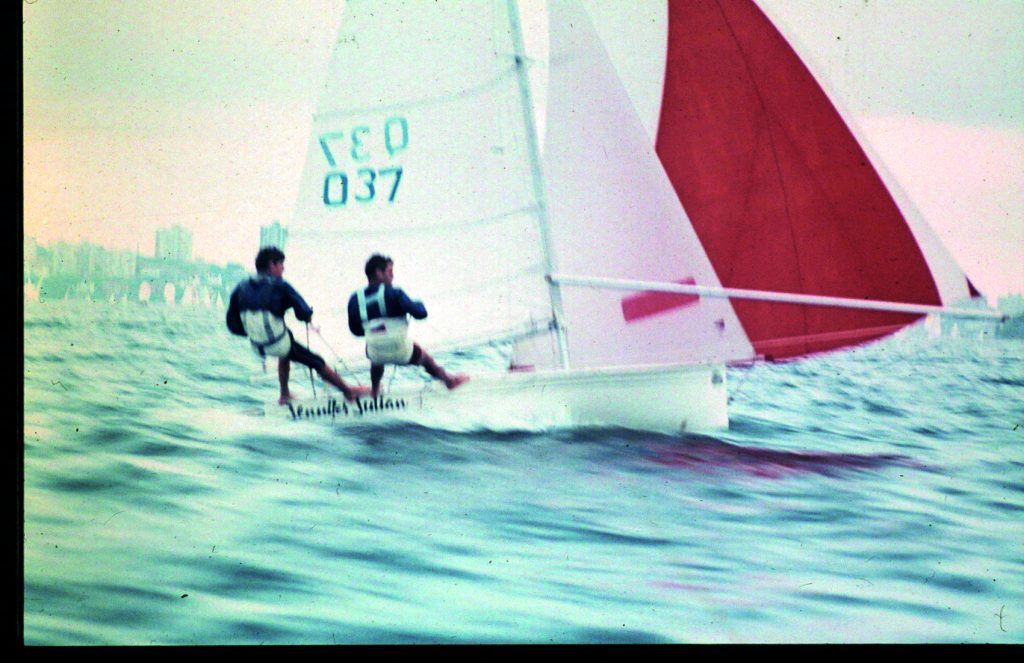

After leaving Auckland Grammar, Bowler began a civil engineering course at ATI, with a part-time job with the Ministry of Works to pay the bills. This allowed him enough free time to design and, with McGlashan, build the 12-footer Jennifer Julian. The then top 12-footer designer/builder John Chapple was a strong influence.

“I sailed a couple of John’s boats, and they were always well balanced.”

The inspiration for the foam sandwich construction came from the late Don Lidgard and Tony Bouzaid’s GRP foam sandwich Miss Hycel. Besides its light and strong GRP/foam construction, Jennifer Julian featured other Bowler innovations: an internal space frame to take the rigging loads, no foredeck, minimal transom, a pocket-luffed main, and having the structure to support twin trapezes.

“When we launched her, she was super quick, but it took us about five races to get her around the course. Once we mastered her, we were pretty much unbeatable.”

Jennifer Julian comfortably won the 1969 Q Class Interdominion trials, then went on to emphatically win the Interdominion Championship and the Silasec Trophy with four firsts and a second place. Incidentally, fourth overall was Bruce Farr and Rob Blackburn in Miss Beazley Homes, while the late Peter Walker and David Hutchinson in Rangi won the Interdominion Javelin title, using a Bowler-designed and built aluminium mast. The Kiwis certainly dominated in Sydney that year.

While McGlashan and Jennifer Julian returned to Auckland, Bowler and Walker headed for Perth by car. There the pair quickly got jobs, and with the Swan River beckoning, hooked up with local Cherub sailors. With the Inaugural Cherub Worlds due to be held in January 1970, the pair designed and built the Cherub Jennifer Julian II in GRP foam sandwich.

“The main reason we used foam sandwich was because we didn’t have any woodworking tools.”

Initially, the Aussie Cherub sailors looked skeptically at the Kiwis with their $400 Cherub, but it was a different tune when Jennifer Julian II won the first race in the Australian Championships. They backed this up with two seconds and a third, which eventually won them the championship after successfully protesting the committee on the way they’d initially scored the countback. The 1970 Cherub Worlds had 48 entries, including seven from New Zealand. It was a hard-fought series, and going into the last race, any one of three boats could have won. However, Bowler and Walker held their nerve and won the Cherub Worlds.

Following stints in London and San Francisco, Bowler headed back to Auckland in 1973 and married teenage sweetheart Lynda (nee Smith). He took up a civil engineer’s position with Kingston Reynolds, Thom and Allardice.

Bowler had hardly touched a boat since Perth, but while he’d been away, Farr’s designs had become dominant. Yachts such as Titus Canby, 727, 45º South, Gerontius, Prospect of Ponsonby, Jiminy Cricket, 45º South II, and others were making the established IOR keelboat designs look pedestrian, while his production yachts – the 727, 1104 and 38, and the Sea Nymph trailer-sailer range – were selling as fast as they could be built.

Farr hadn’t forgotten his dinghy roots either, and his 12- and 18-footer designs were top of their respective classes. Watching the 18-foot fleet in Auckland inspired Bowler back into yachting. With the aid of some sponsorship from WD & HO Wills, he started designing and building an 18-footer.

“I’d always looked at the 18-footers as a wonderful class to be involved with.”

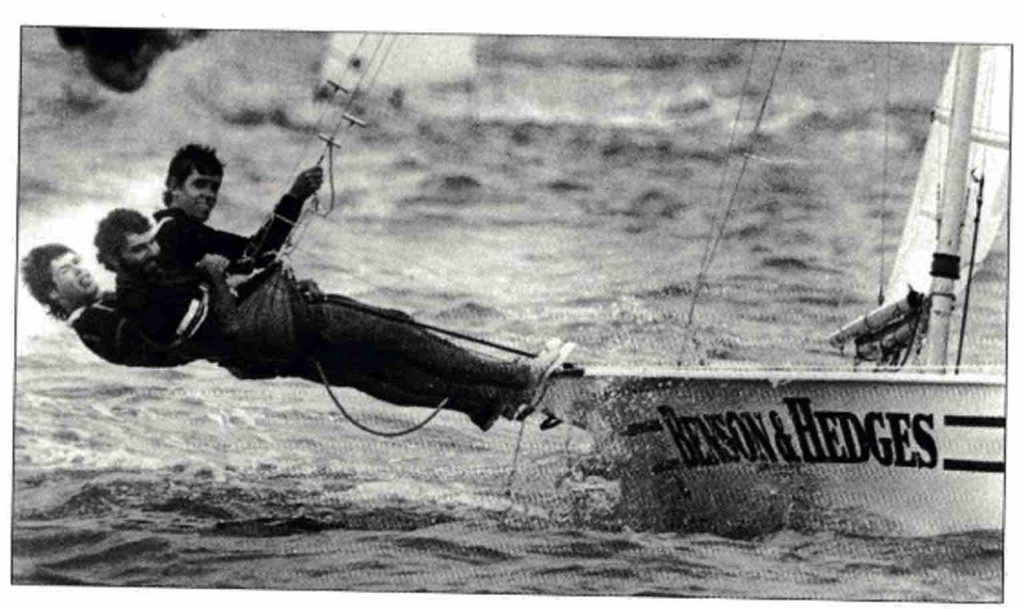

However, Bowler was behind the eight-ball compared to Farr, and it took two boats before his third, Benson and Hedges, crewed by Graham Catley and Simon Ellis, proved competitive. Even so, breakages during the 1977 and 1978 seasons kept them off the podium. With a demanding job and a young family to support, Bowler was struggling to find time and money for top level sailing.

In a different way, Farr was also struggling. Even with the addition of Roger Hill and Walker, Farr was finding it difficult to keep up with demand and asked Bowler to help out with some of the engineering on a consulting basis. Friendly rivals on the water, the pair soon found they enjoyed working together.

Around 1980, Bowler received a bonus cheque from Kingston Reynolds, which had been pruned with the then 66% tax on bonuses. Bowler began thinking that joining a smaller practice would allow him to take advantage of legitimate tax credits. He was looking around for a suitable opportunity when in 1981 Farr offered him a job, and so Bowler joined Bruce Farr Yacht Designs (BFYD).

“I thought I’d like to try it for a time and see how it went. I joined this tiny team of Bruce, Peter and Roger.”

In his first week there, Bowler joined the team to visit their latest creation, the stunning 19.8m Ceramco New Zealand, designed for the late Peter Blake (later Sir Peter) for the 1981-82 Whitbread. Farr had designed another yacht for this race, for Swiss sailor Pierre Fehlmann, which became Disque d’Or. These two designs marked the start of Farr’s decades of dominance around the world yacht racing.

With growing interest from potential international clients, within six months of Bowler joining, the BFYD team began discussing whether they wanted to remain in New Zealand or shift offshore and potentially get into world markets, especially production yachts.

After due diligence, BFYD relocated their entire office to Annapolis, Maryland on the US east coast, which was far closer to all the major production builders in the USA and Europe. BFYD became Bruce Farr & Associates (BFA), with Bowler becoming a shareholder. Walker didn’t make the shift and remained in Auckland.

“There was a world recession on, and it took us a while to break into the market. I kept an eye on the back door as an exit for a time.”

It took 18 months before the move began to pay off. Farr designs started winning on IOR again, spearheaded by their IOR one-tonner design Free Fall. Wellingtonian Geoff Stagg had joined BFA soon after the shift to Annapolis and worked as

a salesman, freeing Farr and Bowler to concentrate on design and engineering.

“Neither Bruce nor I was a salesperson, so Geoff took on that role. It was a successful combination, and it worked really well.”

Meantime, Disque d’Or had finished a creditable fourth on handicap in the Whitbread, whilst the highly fancied Ceramco, after losing her rig on the first leg, still managed 11th on handicap. Nevertheless, both boats had shown their potential in the Southern Ocean, and Fehlmann returned with a commission for a maxi for the 1985/86 Whitbread, which became UBS Switzerland.

“That was a very significant boat for us, the first totally composite maxi.”

Until then no one had designed a maxi constructed from a foam-carbon-kevlar sandwich. Bowler, in combination with Du Pont and Richard Honey from High Modulus, engineered the lightweight construction, allowing a better ballast ratio and an internal aluminium space frame for the rigging loads. Farr did two similar designs for the same race – Atlantic Privateer, for Padda Kuttel and NZI Enterprise for the late Digby Taylor. UBS Switzerland won the Whitbread comfortably by two days.

“It was a big one for us. UBS just smothered the opposition.”

Then came BFA involvement in the America’s Cup (AC). The idea of New Zealand challenging for the America’s Cup had been floating around for many years but was never taken seriously. However, Alan Bond’s 1983 win meant the 1987 event would be held in Perth, and a New Zealand challenge started to take shape.

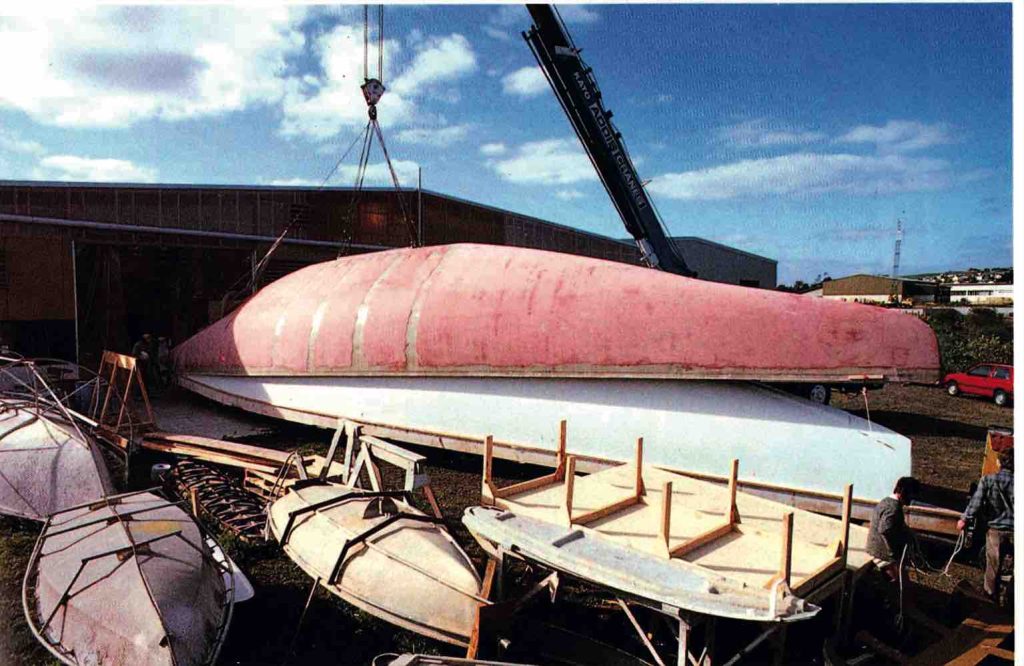

While this column has previously detailed the 1987 New Zealand Challenge, what hasn’t been specifically acknowledged is Bowler’s contribution to the campaign, specifically building the first 12m yachts in GRP/foam.

Since 1980, the International Yacht Racing Union (IYRU) had allowed 12m yachts to be built in aluminium, timber or GRP. A stumbling block for GRP was the requirement that

a GRP 12m yacht must not have a more beneficial weight, or weight distribution, than one built from aluminium.

Several syndicates had investigated the use of GRP, and all had concluded that, due to Lloyds strict aluminium scantling specifications for 12m yachts, GRP construction would not provide advantages worth the trouble. This was based on the material moduli comparison that aluminium was stiffer than GRP.

Bowler was not convinced this assumption was valid, as the complex shape of a 12m yacht potentially made it stiffer. Additionally, a GRP 12m would require far less fairing, and thanks to the use of a mould, two identical boats could be built more quickly. Given Perth’s boisterous conditions and the tight timeframe, these were significant advantages.

Bowler, with the support of the other designers, Farr, Ron Holland and the late Laurie Davidson, took on the responsibility to obtain Lloyds approval for a GRP 12m yacht.

“After talking to Lloyds, it became apparent to me that no one had ever done a weight calculation or weight distribution for aluminium construction, so we had to do that first.”

This meant designing the lightest possible aluminium 12m yacht, gaining approval for that, redesigning it in GRP, then convincing Lloyds that the GRP version would have the same weight and weight distribution as the aluminium one.

Bowler received considerable help from Bill Green from Green Marine, plus Honey and Brian Jones from High Modulus.

“The more we looked at GRP, the more attractive it seemed. For instance, it would be fairer and, because of Lloyds’ deck scantlings, very little extra reinforcing under the fittings.”

The pressure was on. Bowler started the Lloyds process in March 1985, and after jumping through countless hoops, obtained Lloyds approval in September. The two identical 12m yachts, KZ3 and KZ5, were built under full-time Lloyds supervision. Finished by December 1985 and transported to Perth weeks later, their first competitive outing was in Perth in February 1986, where both yachts made an immediate impression on the water.

As has been detailed in several previous columns, the third and final design, KZ7, also built under full-time Lloyds supervision, came within a whisker of beating Denis Conner’s Liberty to win the Louis Vuitton Cup. Conner went on to win the 1987 AC itself. Although no one knew it at the time, the trio of New Zealand GRP 12m yachts marked the end of an era – every AC since then has been raced in yachts built in GRP/composite.