Previously, the AC winner and Challenger of Record had notified the terms and conditions for the next AC promptly after the last race. However, the 1987 winner, Dennis Conner and the San Diego Yacht Club (SDYC), stalled for months over setting the conditions for the next AC, frustrating enthusiastic potential challengers.

This stalling gave Fay the opportunity to mount a challenge under the AC Deed of Gift, which allowed “any organised yacht club” to present a challenge by nominating the dimensions of their yacht, whereupon the defender would have 10 months to build their own yacht for a best-of-three race series.

In July 1987, Fay, Andrew Johns, Tom Schnackenberg, Bruce Farr, and Russell Bowler presented a Deed of Gift challenge with the largest allowable sloop. This was an enlarged version of the European Lake Boats Farr had previously designed for several Italian clients. Designed and engineered by Farr and Bowler, with assistance from Mike Drummond, Richard Honey, Brian Jones, and Richard Karn, what became KZ1 was then the largest composite yacht ever built.

“For Bruce and me this was tantalising job, designing the fastest possible sloop, 90 feet on the waterline.”

Built by Marten Marine (founder Steve Marten), who’d built the trio of 12m GRP yachts, KZ1 was 40.5m loa, 27.4m lwl, with a 4.3m waterline beam, 7.9m overall beam, a displacement of 37,648kg and a massive 1,609m2 of sail.

Leaving aside the futuristic concept of what was then the largest racing sloop in the world, solely in terms of engineering, Bowler was pushing well into unknown territory.

“I look back on that now in horror and wonder what we were thinking – no one had ever built anything like that before. I’m just thankful we got around the course without issues.”

Dennis Conner and SDYD quickly realised they couldn’t design, engineer or build a competitive yacht that size. That they instead chose to build and compete in an 18.2m catamaran is a massive compliment to Farr’s design and Bowler’s engineering. As most readers will recall, the New Zealand Challenge lost on the water two nil, won the resultant court case, and was awarded the AC, but lost it following SDYC’s appeal to the Supreme Court by a vote of five to two.

The only good thing to come out of the Deed of Gift Challenge and its legal shenanigans was the adoption of a new AC class of yacht, which was used for the next five events.

Still keen for another crack, Fay again commissioned Farr and Bowler to design multiple yachts for his 1992 attempt with the new AC class. These boats became NZL10, 12, 14, and 20, the latter sporting tandem keels.

The concept of twin moveable keels wasn’t new and theoretically promised significant performance gains, but no one had ever made the concept work properly. Consider the engineering involved in twin rotating foils having to support a 16,000kg lead bulb whilst retaining full movement! Bowler, Steven Morris, and Neil Wilkinson not only made the twin keels work, but arguably NZL20 was the quickest challenger at the 1992 event.

NZL20 went into the Louis Vuitton (LV) final as the favourite against the Italian Il Moro. Sadly, from 4:1 up on the water, the Italian syndicate convinced the jury that NZL20’s bowsprit was being used illegally, dropping the result to 3:1. The IYRU overturned this ruling some months later, but too late for NZL20. Il Moro won the LV Cup five to three. However, the defender, Bill Koch’s Cuban syndicate, was very strong and whitewashed the Italians four to one.

“Looking back, Bill had all his bases covered, and he had access to computer programs predicting performance in waves. Narrow [beam] was the place to be, and it’s doubtful we would have beaten him.”

After being passed over by the late Peter Blake (later Sir Peter), Farr and Bowler were approached by Chris Dickson to design a yacht for the 1995 AC. Compared to most other syndicates, Dickson’s funding was miniscule, and a late start meant design time was limited. Additionally, the crew was effectively the New Zealand B team. Despite all these limitations, TAG Heuer still finished third in the LV Cup, an excellent result.

“Poor old Chris, he got scuttled on the fundraising front, and it was amazing he did as well as he did. It was an interesting boat.”

For the 2000 AC, Farr and Bowler were approached by the New York Yacht Club’s PACT2000 team to design two boats, USA 53 and 58.

“We were pretty excited to get that commission, and it began very well. Then a couple of other [American] challengers started stealing our sponsors, and we didn’t get the resources we were expecting.”

While the Pact2000 challenge was one of the favourites, in November 1999, USA 53 folded in half. Although the boat was salvaged and racing continued in USA 58, the syndicate didn’t make the semifinals.

“The structural design was between myself and Dirk Kramers and had a thick cored deck to make the yacht really stiff longitudinally. However, there was a latent weakness in the bonding of the skins to the core. The crew repaired a section of the deck that had delaminated, but instead of a 700mm scarf, they only used 70mm. Due to budget constraints, neither Dirk nor I was involved in the repair, and it’s amazing the yacht got around the course as far as it did.”

Farr and Bowler were being courted by the Italians for the 2003 AC, when Larry Ellison asked them to design an AC for him. Ellison was an existing client, Farr and Bowler having previously designed the ILC maxi Sayonara for him.

“Bruce and I were keen to go with the Italians, but the call from Larry was about the only call that would have stopped us.”

Ellison commissioned Farr and Bowler to design AC boats for both the 2003 and 2007 AC events. However, while their boats were quick, they were a fraction off the pace.

In 2003, Oracle lost the final of the LV Cup against Alinghi 5:1, and in 2007, lost against Luna Rossa in the semifinals of the LV.

So, despite coming close on several occasions, Farr and Bowler couldn’t add an AC win to their trophy cabinet.

Results, however, were hugely better in the Whitbread/Volvo Around the World Races. Hot on their success with UBS Switzerland in 1983-4 Whitbread, the Farr Office had four IOR maxi clients for the 1989-90 event: Grant Dalton, Skip Novak, Pierre Fehlmann, and Blake.

Leaving aside the design innovations such as ketch rigs, Bowler’s innovative and lightweight engineering broke considerable new ground. The four maxi composite hulls were so light that a significant amount of ballast was required to bring them to their designed displacement. This was achieved with a cast lead section fitted into a hole in the hull, and through which the keel was bolted, an elegant and strong solution.

“The IOR rule to which these boats were designed was out of date for modern composite structures. I think Bruce was very clever at conjuring up the right requirements. When you look back, it was a wonderful race to be involved with.”

In the 1989-90 Whitbread, Farr/Bowler maxis finished one, two, three, and five. For 1993-4 Whitbread, Farr/Bowler designed three maxis and seven of the then-new W60 class – an astounding 10 boats out of 14 in the race. The top eight boats to finish were all Farr/Bowler, with nine of them in the top 10. Farr/Bowler W60 designs featured in eight of 10 entries in the 1997-8 race, six out of eight in the 2001-2 event, four out of seven in the 2005-6 event, two out of eight in the 2008-9 event, and two out of six in the 2011-12 event.

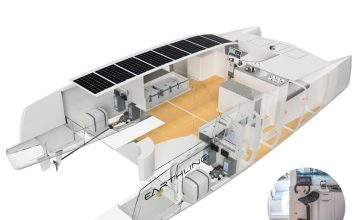

Incidentally, Bowler’s last project at Farr Yacht Design was completing the engineering of the then-new one-design class for Volvo Ocean Race, the Farr 65. The yachts were built by four boatyards: Decision in Switzerland, Persico in Italy, Multiplast in France, with Green Marine in the UK doing the final assembly.

The Farr 65s have sailed many thousands of miles since their first trip around the world in 2014-15. They were used for 2017-18 and 2023 world events, as well as annual European ocean racing events. Their next around-the-world ocean event will begin in January 2027.

“Those boats have been wonderful; they all go the same speed, they’ve all been around the world several times, and except for one that ran into a reef at 19 knots, they’ve all lived to tell the tale.”

Between them, Farr and Bowler have been by far the most successful designer for this race – ever. Space prevents listing all the other Farr/Bowler racing successes; suffice to say, during the 1980s and 1990s, they were the dominant race boat designers in the world at all levels.

The Farr/Bowler partnership has also been equally successful when designing production yachts.

“Bruce got his feet wet with Sea Nymph with the Farr trailer-sailers. Fantastic little boats, brilliant pieces of industrial design.”

In New Zealand, the Farr/Bowler partnership created the Farr 1020 and 1220 for Sea Nymph and the Farr 38 for Compass Yachts. Following the move to Annapolis, they were commissioned to design the Beneteau First 45F5. Unveiled in 1989, the 45Fs became a huge success. Other production yachts followed, including the Oceanis 440, the Moorings 445, 53F5, 42F7, the Beneteau 40.7 and 64, others for Jeanneau and Bavaria, and the one-design Mumm 36.

When engineering production yachts, Bowler had to shift focus from saving weight to ease of production and longevity.

“Most of the production boats went into the charter market, so they had to be rugged. It’s totally different. A lot of the engineering is about ease of construction during assembly, and in some areas you have to be conservative.”

Bowler retired from Farr Yacht Design at the end of 2012, but was persuaded to return to work by Iain Murray for the 2013 AC in San Francisco to review the structural engineering of all the team’s boats. This was a US Coastguard requirement following the death of Artemis crew member Andrew (Bart) Simpson during the lead-up to the LV Cup.

“Initially, I was apprehensive of the task. Fortunately, the various engineers had started to talk to each other about the loads, which made the task relatively straightforward.”

For the 2017 AC, Bowler was asked by Murray to help the official measurer, Ken McAlpine, with measuring the AC 50 catamarans.

“That was a wonderful experience and my last involvement in top-level yacht engineering. And no one’s phoned me since,” Bowler said with a chuckle.

Since then, Bowler has enjoyed his retirement. With a child in each city, the Bowlers spend half the year in Annapolis, the other half in Auckland.

These days Bowler’s main involvement with boating is racing Cocktail Class Skua powerboats. These 2.4m racing craft were designed by the late Charles MacGregor in 1939, and motive power is restricted to 6 to 8hp outboards.

Bowler’s three favourite designs are:

UBS Switzerland:

“That was a real breakthrough design for us and we worked hard on that boat.”

The Big Boat:

“That was wonderful. Politically it achieved heaps, it’s a piece of history, but that’s all it is.”

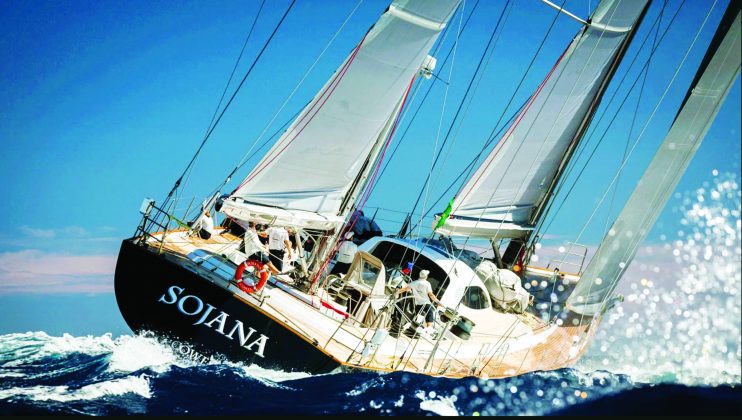

Sojana:

“A 32.9m cruising superyacht ketch for the late Peter Harrison, that was an interesting commission, and it’s been a really good yacht.”

“I’ve been doing this for 14 years now, it’s lots of fun.”

Bowler started his boat engineering with a foam sandwich Cherub and, together with Bruce Farr’s designing abilities, over the next three decades led the transformation from bucket and stick to the sophisticated and highly complex composite technology we enjoy today.

It’s a long way from a P Class on Lake Rotoma to world dominance, and Russ Bowler is a wonderful inspiration to anyone with a burning desire to achieve. We wish you a long and happy retirement Russ, you’ve more than earned it.