It’s early Sunday morning, June 17, 1984, and solo sailor John Mansell awakes to a strange motion from his 11m catamaran Double Brown.

Something’s not right, and it doesn’t take him long to discover his catamaran’s main and aft aluminium beams have cracked almost right through. Mansell’s in the middle of the North Atlantic, on the edge of the Grand Banks, and sailing further is impossible. Reluctantly, he decides his only option is to abandon ship. After all the work and expense of getting to the start line, it’s a bitter blow.

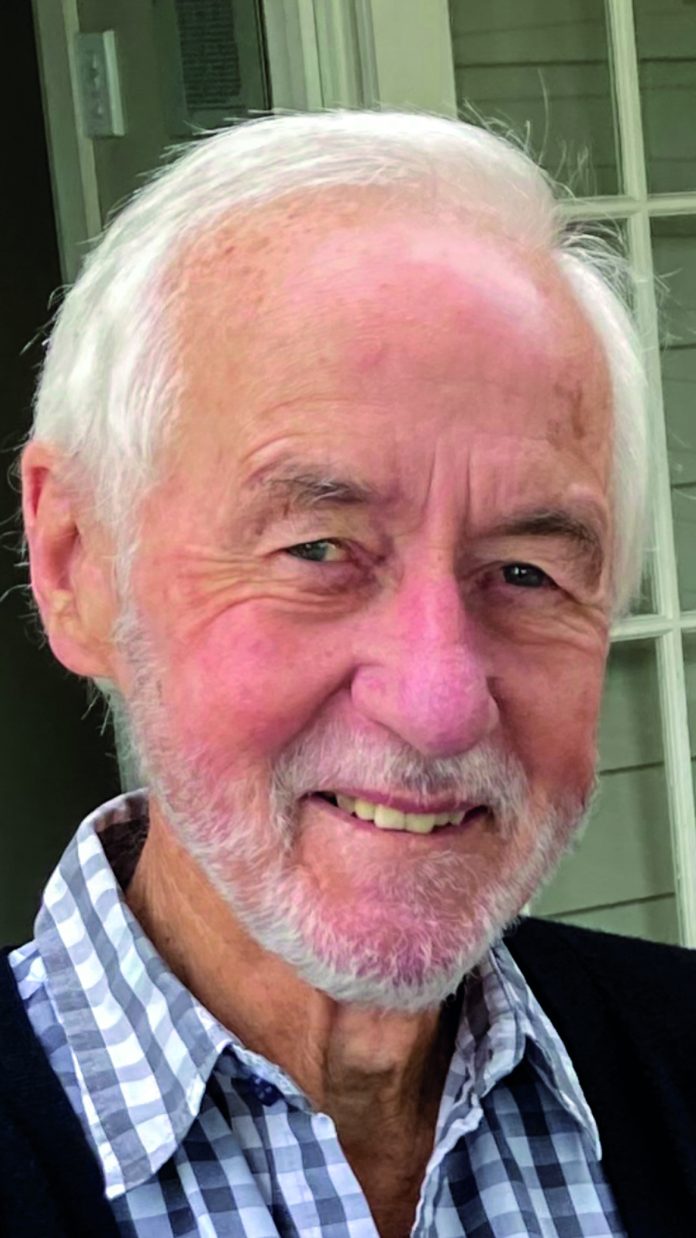

Mansell’s story begins in 1942 with his birth mother’s brief wartime romance, which a little over nine months later, saw him adopted by a kindly Lower Hutt couple.

“A very nice family, very decent, hard-working people.”

Aged eight, Mansell’s uncle took him sailing in an Idle Along on Paremata Harbour, kickstarting his interest in sailing.

“I have vivid memories of the experience, and that got me thinking about sailing. But we had little money; we had to wait.”

After seeing all the ships tied up at Wellington’s wharves, Mansell began thinking about shipping as a career. In those days the Union Steamship Company (USSCo) offered cadetships, the marine equivalent of an apprenticeship. However, Mansell had to front up with £200 to apply, a considerable sum in post-WWII New Zealand, which he earned working as a labourer. He joined the USSCo as a cadet in 1958.

At the time, the USSCo owned 65 ships and, besides coastal routes, serviced India, Australia and North America.

“It was a great life, and I must have crossed the Tasman at least 50 times.”

By the end of his four-year indenture, Mansell qualified as a second mate. In 1963 he joined Shaw, Savill and Co, then after three years with them transferred to their subsidiary company, Crusader Line, where he spent the next three years on ships trading in the Pacific.

“That was the highlight of my deep-sea career.”

During this time, Mansell taught himself to sail using a little Swedish sailing dinghy that was aboard one of the ships. He obtained his first mate’s certificate in 1964 and his master mariner’s certificate in 1968. Mansell also met and, in 1965, married Mary, with whom he had two sons: James and Matthew.

In 1968, he took a shore position in Australia with Shaw, Savill, before the couple moved to Nelson, where Mansell worked briefly on trawlers fishing the West Coast. After an 18-month stint with Seatrans on the Japan to New Zealand run, he obtained a second mate’s position on the Cook Strait ferries, which had just been taken over by New Zealand Rail.

By now, Mansell was seriously into sailing and, after a Z-class, bought the 5.7m clinker bilge keeler Shoestring. Dreaming of something bigger, Mansell purchased the plans for a Nova 28 from Alan Wright, which he had built by Roy Talbot in Nelson. Mansell considerably modified the design, raising the topsides 150mm, adding a heavily cambered flush deck and 600lb (272kg) of extra ballast, all done with Wright’s approval.

“I wanted something very rugged that could withstand a knockdown.”

Mansell’s friend and fellow rail ferry master, the late Peter Petherbridge, went halves in the yacht they named Innovator, launched in 1973.

Mansell entered the 1974 Trans-Tasman race, which was only the second time it had been run. There were 10 starters, of whom eight finished, and the start was held in a very strong sou-easterly. The late Bill Belcher won the race in his 7.4m Raha, with Mansell finishing fourth on the line and third on handicap.

With this under his belt, in 1976 Mansell became the first New Zealander to enter the Observer Singlehanded Trans-Atlantic Race (OSTAR) in a Kiwi-designed and built yacht. Before the race, Mansell had carried out a full refit, including a new rig and sails, a new Volvo engine, and an Aries self-steering system. The yacht was renamed Innovative of Mana in recognition of all the support from the Mana Cruising Club. Thanks to his shipping contacts, including the late Harry Julian, Mansell was able to secure free shipping for Innovator of Mana to the UK and back from New York.

The 1976 OSTAR attracted 125 entrants, and as there were no size restrictions, a number of entrants opted for waterline length. The biggest entrant, Club Mediterranee, had an LOA of 72m. Innovator of Mana was one of the smallest entrants, in the Jester Class up to 11.6m.

Mansell followed the great circle route, the most direct course up to 56o North. The wind was constantly on the nose, and he encountered four gales. However, the Nova handled the conditions well and would happily lie ahull when required. The latter part of the crossing was over the Grand Banks, an area notorious for fog, icebergs and light weather. The ten days of heavy fog he endured was an issue.

“It was unnerving hearing ships’ foghorns close by and smelling their funnel smoke but not seeing them.”

Mansell’s elapsed time was a respectable 35 days, 12 hours, and he finished 21st out of 52 finishers in Jester Class, and 12th overall on handicap. It had been a tough race – there were 50 retirements, including two deaths.

“Overall, it was a wonderful experience, and I was really glad I’d done it.”

Afterwards, Innovator of Mana was shipped back to New Zealand.

In 1977 Mansell and Petherbridge entered the yacht in the first Two Handed Around the North Island Race (RNI), where they finished eighth out of 39.

Afterwards, the pair kept Innovator of Mana in Auckland for some months. In July 1977 Mansell single-handed Innovator of Mana back to Wellington down the east coast, but an unforecasted 75-knot SW storm forced him to lie ahull and drift NE. Twenty-four hours later, off the Ritchie Banks, Hawkes Bay, a series of knockdowns forced Mansell to steer downwind. Six hours later, Innovator of Mana was pitchpoled, and Mansell broke his leg. He and the undamaged yacht were towed to Gisborne by a large trawler and Petherbridge sailed her back to Wellington some weeks later.

Mansell sold Innovator of Mana a year later, as he was planning to enter the 1980 OSTAR. Mansell commissioned Wright to design a fast custom yacht for the Jester Class; a flush-decked yacht 11.6m loa, and 8.5m lwl. However, funding proved difficult, and the idea was shelved.

Instead, Mansell founded a navigation teaching business, initially using a friend’s yacht. When the concept proved successful, he had Wright redraw his OSTAR design with a longer waterline and a conventional cabin, which – built by Bruce Hicks – became Navigator. Besides using Navigator for his navigation training school, Mansell sailed her in the 1983 Auckland to Suva Race.

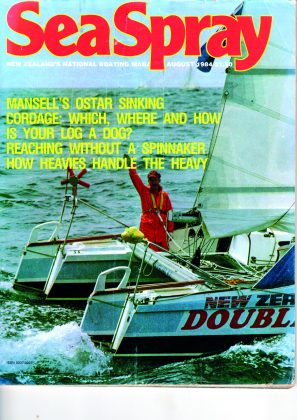

However, Mansell was still keen for another crack at the OSTAR and discovered the late Ron Given’s 11m catamaran Tigress for sale. Designed as a cruiser/racer, Tigress was then one of the few multihulls in New Zealand capable of a Trans-Atlantic race. After buying Tigress from Given and renaming her New Zealand Challenger, Mansell, Given and two experienced Paper Tiger skippers raced the yacht in the 1983 Coastal Classic, one of the roughest races on record. Many fancied boats, including pre-race favourite Sundreamer, pulled out, and Mansell won comfortably.

“The yacht went very well to windward, and that race was mostly hard on the wind.”

Leveraging off this result, Mansell secured sponsorship from DB Breweries, and the catamaran was renamed Double Brown. With Given and two crew, Mansell sailed Double Brown to Nelson down the West Coast, then single-handed her back to Auckland for his OSTAR qualification. Around the same time, his marriage to Mary ended, and the couple went their separate ways.

“I was not in a good emotional state on that trip to Auckland. But I got over that; you have to.”

Once again, thanks to his shipping contacts, Mansell was able to have Double Brown shipped to England free of charge. Mansell had entered Class 4, under 10.66m, and after the first six days was leading the other 20 boats in the class. Unfortunately, Double Brown’s main halyard broke, and Mansell lost the spare he had rigged in Plymouth. He was forced to heave to and scale the mast at midnight to rig a replacement. During this time, Mansell discovered the inner gunwales of the hulls had developed cracks, and one of the bolts holding the main beam to a hull had worked loose.

Unable to fully tighten the bolt, Mansell lashed the hull down onto the beam mounts, which cost more time. Then, a week later, and still on track to finish in under 21 days, came the events described in the opening paragraph.

“There was no way I could keep racing; the boat was shot.”

Mansell had no choice but to radio for rescue, which was carried out by fellow competitor the late Alan Thomas in his Class 3 monohull, Jemima Nicholas.

“He was only three or four hours away, so it was pretty quick.”

With Mansell aboard but not helping in any way, Thomas finished 10th in Class 3. A chastened Mansell flew home from New York boatless, and Double Brown was never seen again.

“She was beautifully built by Ron, and it was such a shame.”

Mansell ran his navigation school for several more years before selling it and his half share in Navigator to Petherbridge. Since then, he has owned quite a few boats – the Farr 920 Farcical, the Carpenter 29 Innovator II, the Lidgard 36 Countdown, the Holman 40 Beyond, the Alden motorsailer Sunquest, and the S&S 44 Trojan Eagle. As an aside, Mansell and Thomas did the Two Man Around Great Britain race on Jemima Nicholas in 1985, and the pair did the 1986 RNI race in Innovator II.

Some years later, Mansell sold Trojan Eagle to the late John Webber, who featured in this column several years ago. Mansell bought Trojan Eagle back in 2022 in partnership with his daughter Lena.

Before this, in 1988, Mansell had married Christina and the couple went on to have three daughters, Anna, Lena and Sofia.

“We’re really lucky that all of our children and grandchildren live ‘over the hill’ in the Hutt Valley and Wellington.”

In 1994, NZ Rail was sold to Wisconsin Rail, and Mansell, who had been a captain for 20 years, was faced with redundancy. With three children under six, he couldn’t afford to retire, so he took a position as Divisional Manager, Maritime Operations, with Maritime New Zealand. His main responsibility was the regulation of all commercial vessels within New Zealand waters. During his time there, Mansell became an authority on international maritime law and, to cut a long story short, achieved a master’s degree and a doctorate on the subject. He has since published two books on maritime law and is currently finishing a third.

“There are still flaws in the regulatory system; hopefully they will be addressed at some stage.”

Mansell retired in 2014 and relocated to Martinborough.

Looking back 50 years, when trans-ocean single-handled racing was still in its infancy, Mansell was the first New Zealander to compete in an OSTAR in Kiwi-designed and built yacht – not once, but twice.

John Mansell, seaman, sailor and navigator extraordinaire. You’ve done this country more than proud.