Update 12:27pm NZ time:

Conrad has just been in touch. Thank goodness he is OK, and (as a second priority to safety) is pushing forwards.

The biggest impact thus far from the total blackout on his IMOCA is that he had to slow down for 24 hours (having just found his wind again after days of painfully slow progress in the doldrums) to complete repairs on the boat.

I will use a direct copy of Conrad’s messages as I think the original text from him contains the brutal reality of single-handed round-the-world racing:

[1/12/2024, 12:22:17 PM] Conrad Colman: Exactly. The panels cooked the boat. The charge controller didn’t do its job. Several components are fried definitely, others I’ve got back by removing diodes on a printed circuit board.

[1/12/2024, 12:22:20 PM] Conrad Colman: The boat blacked out when I was in full attack mode, all the sails up in 20 knots. I managed to drop the spinnaker and roll the j3 jib while sailing without autopilot. Then stopped the boat and went into Mr fix-it mode

[1/12/2024, 12:22:22 PM] Conrad Colman: I have spares, but have now used them all. I’m in a knife’s edge for the rest of the race

[1/12/2024, 12:23:32 PM] Chris Woodhams: You cannot get more supplies – such as a solar controller

[1/12/2024, 12:23:47 PM] Conrad Colman: It’s OK. To sum up I had to stop the boat for several hours and then sail very underpowered for a day more while I was working on the boat. It’s frustrating to have lost lots of miles relative to my competitive, but it looks like for the moment. I’m still in the race.

Original report below

The incident occurred as Colman, sailing at nearly 20 knots under spinnaker, neared the Cape of Good Hope. At 1530 UTC, an electrical overload caused multiple systems to fail, leaving him without crucial navigational and operational capabilities.

A race against time

The severity of the blackout required Colman to halt progress, secure the boat, and attempt urgent repairs. Long hours of effort through Friday night have partially restored some functionality, but key systems remain offline, including his main autopilot and Starlink communications used for sending large video files—a vital lifeline for both safety and race reporting.

Colman’s situation is particularly precarious in the remote and unforgiving South Atlantic, where mechanical resilience and mental fortitude are paramount. While his boat is back on course, it is now operating in a compromised state, raising significant challenges for the days ahead.

A sailor’s resolve

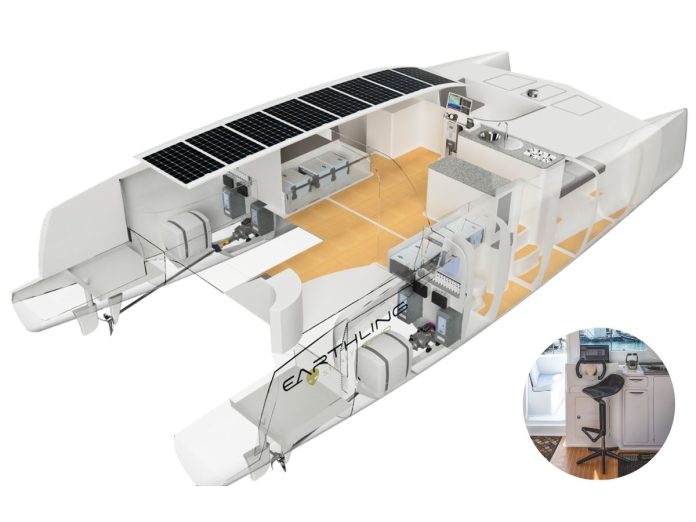

Despite the adversity, Colman’s trademark positivity shines through – and his ‘Number 8 Wire’ mentality has kicked in to solve the issue. I had just been talking to Conrad (Chris from Boating NZ) on the various systems aboard – everything is duplicated, such as power and autopilot: from what I know from discussions yesterday and over the past weeks, he has active and stand-by power supplies which he can manage as required. While having backups to the autopilot et al, the description, brief as it is from Vendée management, is one of power failure, suggesting he will start on the power system fix immediately.

Early Saturday morning (Europe time), he sent an update alongside a photo of a spectacular sunrise, declaring: “It’s a new day.” His optimism is a testament to his unyielding determination and the spirit of the Vendée Globe—a race that has always demanded the extraordinary from its participants.

Support network activated

Colman remains in constant contact with his shore team and Vendée Globe race management, ensuring updates on the repairs and his safety. The team is monitoring the situation closely, offering technical advice and emotional support as he navigates this critical phase of the race.

What’s at stake?

Currently positioned 37th in the fleet, Colman’s situation underlines the immense challenges of solo offshore racing, where even minor technical failures can have dire consequences. The Vendée Globe, often referred to as the “Everest of the Seas,” tests every aspect of a sailor’s ability—from physical stamina and seamanship to mental resilience.

For Colman, the loss of autopilot is particularly troubling as it forces him to hand-steer the yacht for extended periods, a physically exhausting task that could compromise his ability to focus on navigation and weather strategy.

The road ahead

While Colman’s indomitable spirit is clear, this technical setback highlights the fragility of the race environment. With the Cape of Good Hope looming and the most challenging Southern Ocean stages yet to come, the pressure is mounting to restore full functionality aboard MS Amlin.

As fans and followers rally behind the Kiwi sailor, this incident serves as a stark reminder of the dangers faced by these intrepid competitors in their quest to conquer the globe. For now, all eyes are on Colman as he works tirelessly to overcome this setback and keep his dream alive.

Stay tuned for updates as the story unfolds. I have messages in with Conrad, I had pinged him earlier today with questions about progress as I had not heard anything for 24 hours which is unusual – then the Vendée update came out informing me of this catastrophe.