On a calm winter morning, tucked behind an industrial roller door near the Tāmaki Estuary, a new kind of boatbuilder is preparing for liftoff. Not with rockets or jets—but with foils, carbon fibre and clever Kiwi engineering.

Vessev, a marine technology startup based in Auckland, is rewriting the rules of boat design. Their goal? High-speed, low-energy, electric-powered foiling vessels that don’t just flirt with sustainability—they deliver it. And not in a distant-future, prototype-on-a-plinth sort of way. These boats are real, in the water, and soon to be in commercial operation.

We were invited inside their factory for a close look at the design, construction and systems that make these boats tick. Then we stepped onboard for a full test ride through the Waitematā Harbour to see what all the quiet fuss is about.

We came away convinced: this isn’t just a new kind of boat. It’s a new kind of boating.

From hands-on craftsmanship to carbon production

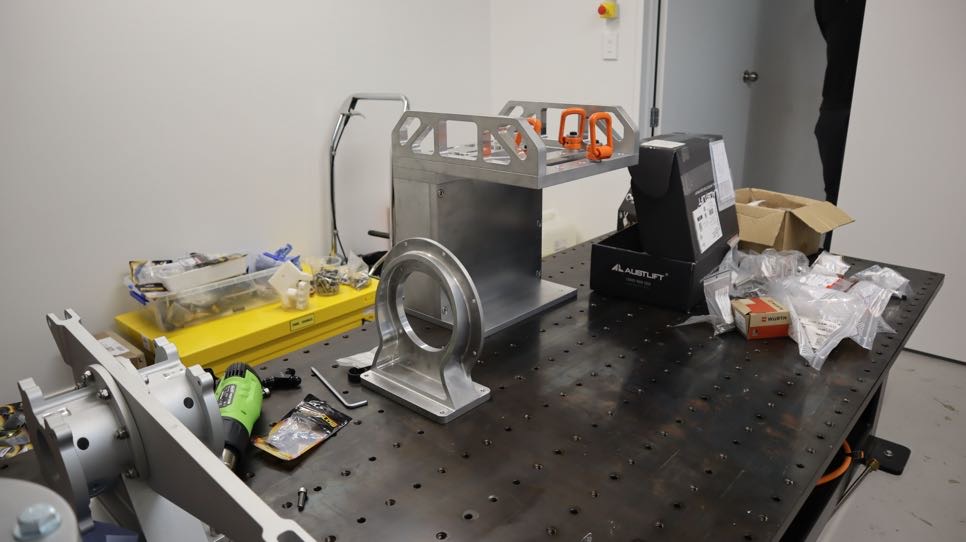

Walking into Vessev’s factory is like entering a hybrid space between a composite workshop and an aircraft hangar. There’s carbon fibre everywhere. Moulds line the floor.

Some are made from hand-glued MDF covered in Teflon—temporary tools from early builds. Others are precise, glossy composite forms destined for a long life and many production runs.

“In the beginning, these boats were artwork,” explains Vessev CEO Eric Laakmann. “Each one was hand-built, one-off. But now we’re building for scale. We’re turning them into products, not just projects.”

The shift to carbon tooling is a big step. Entire hulls and topsides will be pulled from dedicated moulds, reducing man-hours and increasing quality. The team is setting up a five-cell assembly line where new vessels will be launched every five weeks.

Radical modularity and smart simplicity

Under the skin, these vessels are anything but traditional. The foils are retractable, modular and built for long-term serviceability. “These aren’t precious tech toys,” says Laakmann. “They’re meant to be used. Anywhere.”

That design philosophy is seen in every component. Each actuator on the boat—there are seven, to manage the rudder, foils and flaps—is based on the same core design. If one fails, a spare can be dropped in without rewiring or recalibrating.

Even the foils themselves are field-serviceable. They bolt apart into manageable sections, each with distinct material transitions between carbon fibre and stainless steel. And there are QR codes printed directly on hardware components that link to teardown instructions, repair guides and spare part lists. It’s more tractor than Tesla—on purpose.

“This isn’t just for New Zealand,” says Laakmann. “We want someone in Palau to be able to service their own boat with a set of spanners and some basic skills.”

Riding the future, today

Our time onboard Vessev’s VS—9, their 9-metre hydrofoiling electric craft, was a quiet revelation.

With three of the Vessev team aboard, plus a couple of lucky guests, we departed the dock with little ceremony—just the soft electric whir of drive components and the slight chop of the Waitematā lapping the hull. Then, as the boat picked up speed, it simply rose.

No shudder. No wall of spray. No ‘we’re foiling now’ moment. It just lifted and kept going.

“You don’t even feel it,” someone said behind us. And they were right.

Once aloft, the experience is surreal. The boat is quiet—eerily so. The usual percussion of waves on hull vanishes. Steering is light. Movement feels frictionless. And perhaps most impressively, it doesn’t matter what the water’s doing underneath. Ferry wakes, cross-chop, or the lingering breeze from an early front—none of it seemed to make a difference. The vessel glided across all of it like a flying carpet with a helm.

The foils are doing all the work

What’s most fascinating is how little the driver has to manage. There’s no foil trimming or computer screen obsession. You steer. You manage speed. That’s it. The rest is handled by the boat.

Vessev’s system uses a distributed ECU layout—each foil has its own mini-computer. Pitch, angle of attack, retraction, and lift control are all managed in real time. The system calculates loads and reactions on the fly. If it needs to adjust, it does.

The ‘Pi Foil,’ as the team calls it, is the backbone of the design. Most of the lift happens at the centre of the span, where flow is cleanest and lift-to-drag ratios are highest. The tips taper deliberately to reduce vortex loss—borrowed straight from glider aerodynamics.

And because everything retracts fully, there’s no need for divers or hardstand haul-outs. “Even a little slime on a foil can kill your efficiency,” one of the engineers reminded us. “Lifting them clear of the water is critical.”

Flexible platforms, custom topsides

Back at the factory, the broader plan came into view. Rather than endless custom builds, Vessev is settling on three main platforms: a 9-metre, a 12-metre, and a soon-to-launch 18-metre capable of carrying 100 passengers.

Each of these will share a core hull and foil system. Above that, the topsides can vary—commuter seating, enforcement gear, aquaculture layouts, even luxury configurations for private owners.

“Everything difficult is in the platform,” said Laakmann. “The rest is just furniture.”

That separation of platform and payload allows for repeatability in manufacturing while still enabling the kind of client-specific tweaks that commercial operators require. It’s a smart approach, and one borrowed from the aviation world.

Vessev’s partnership with Fullers is already proving the concept, and international interest is growing—particularly from the US and UK. Moulds may soon be shipped abroad. Software and foil packages could be licensed to other builders. In time, Vessev may not be the only name on these vessels. But their technology will be the one making them fly.

Building boats—for now

For all the carbon fibre, actuators and composite tooling inside the Vessev factory, one message from Laakmann stood out: building boats is only part of the picture.

“We’re more like a marine technology manufacturer,” he said. “We build boats as well, but we build boats because it’s the only way to integrate our technology for now. But in the long arc, like, there’s no reason we can’t be providing our technology to other boat builders out there.”

Vessev’s true value lies in its intellectual property—hydrofoil design, stability control algorithms, distributed computing, and control software. As Laakmann put it:

“That’s how you get scale. Boats are unique and special snowflakes. And the reality is that we aren’t going to be able to serve every market on our own.”

He likens the model to Apple whom he previously worked with:

“Apple does very little of their own manufacturing. Apple’s a design company. They partner with manufacturers to create their hardware. We’re not Apple yet… but in the long arc of it, we could start deploying some of those tactics.”

Whether working with third-party builders using Vessev’s designs, or licensing foil and software systems for integration into existing hulls, the company’s strategic vision is clear: to be the marine tech engine powering a global fleet of next-generation boats.

Propulsion 2.0—coming soon

While much of our visit focused on hulls, foils and onboard systems, we were also given a glimpse of the next leap in Vessev’s development: a fully integrated propulsion system designed from the ground up for electric foiling.

We’re not spilling the details yet, but let’s just say the new tech marks a major step forward in efficiency, cooling, and system simplicity. It’s set to debut in July—and we’ll have a deep dive in the next issue of Boating New Zealand.

Final thoughts

What Vessev is building isn’t a toy for the rich, or a fragile showpiece for boat shows. It’s a scalable, serviceable, and surprisingly elegant solution to a modern maritime problem: how do we go faster, cleaner, and cheaper—without making the sea a mess?

The answer, it seems, is to rise above it.

Vessev’s boats are foiling, flying, and quietly rewriting what we expect from the water. Whether they’re ferrying passengers, patrolling coastlines, or simply giving someone the ride of their life, one thing is clear: the future has already left the dock.