Beneath the North Sea

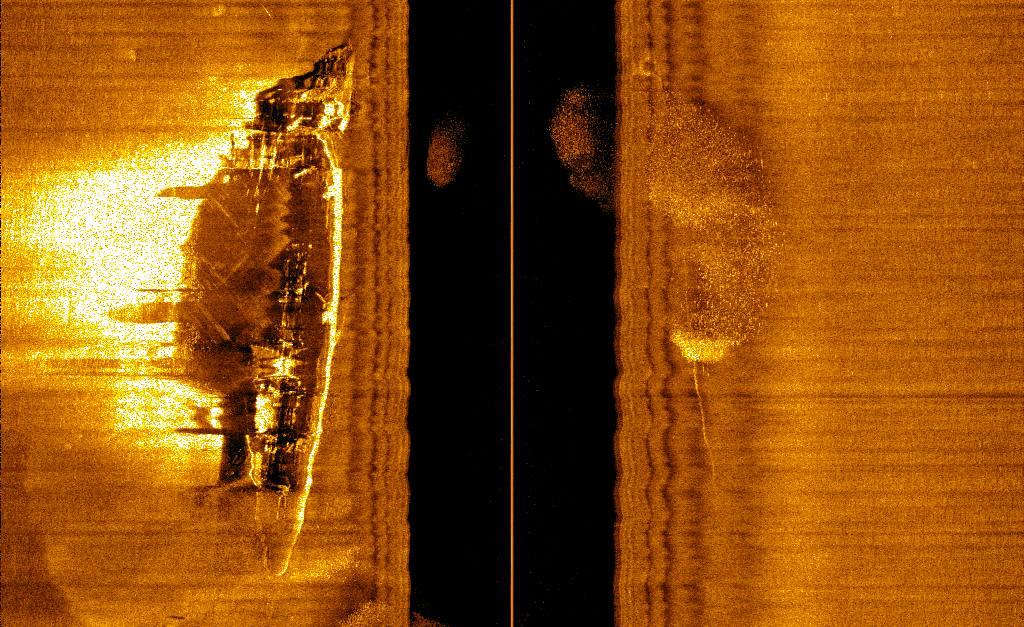

On a grey morning in April 2025, sonar screens onboard the explorer MV Jacob George lit up with the unmistakable outline of a warship: long, narrow, lying bow to the north, 82 metres deep. After more than a century missing, the final resting place of HMS Nottingham, sunk in battle during the WWI, had been found.

The discovery was the culmination of meticulous archival research, a risky offshore sonar expedition, and weeks of planning by the ProjectXplore team, a group of Global Underwater Explorers divers, researchers, and technicians led by Dan McMullen and Leo Fielding.

“She’s one of the best-preserved WWI cruisers ever located,” said McMullen. “We knew within minutes of seeing her armament layout and funnel arrangement, and then seeing ‘NOTTINGHAM’ embossed on the stern, that we’d found her.”

The HMS Nottingham

Commissioned in 1914, HMS Nottingham was one of three Birmingham-class cruisers built to scout, screen, and support the Royal Navy’s global operations. At 139 metres long and displacing over 5,400 tonnes, she was fast, well-armed with nine 6-inch guns, and could range more than 4,000 nautical miles at 16 knots. Her distinctive thin–thick–thick–thin funnel configuration marked her out among the famed ‘Town’-class group, widely considered the best cruisers of WWI.

She was a veteran of the battles of Heligoland Bight, Dogger Bank, and Jutland. At Jutland in 1916, Nottingham and her squadron surprised a German cruiser group in close-quarters combat, opening fire at near point-blank range. “They were very close, and clearly on a converging course,” wrote British war historian Henry Newbolt. “In a quarter of an hour it was all over.” That action showcased Nottingham‘s firepower and agility.

But just months later, Nottingham would be lost to one of the most daring submarine ambushes of the war.

The last push to Sunderland, the last stand of HMS Nottingham

On the night of 18 August 1916, German naval intelligence believed it had a window to strike against the great British Navy. The entire German High Seas Fleet, less one squadron, put to sea under cover of darkness; their goal, to bombard the industrial city of Sunderland on England’s northeast coast.

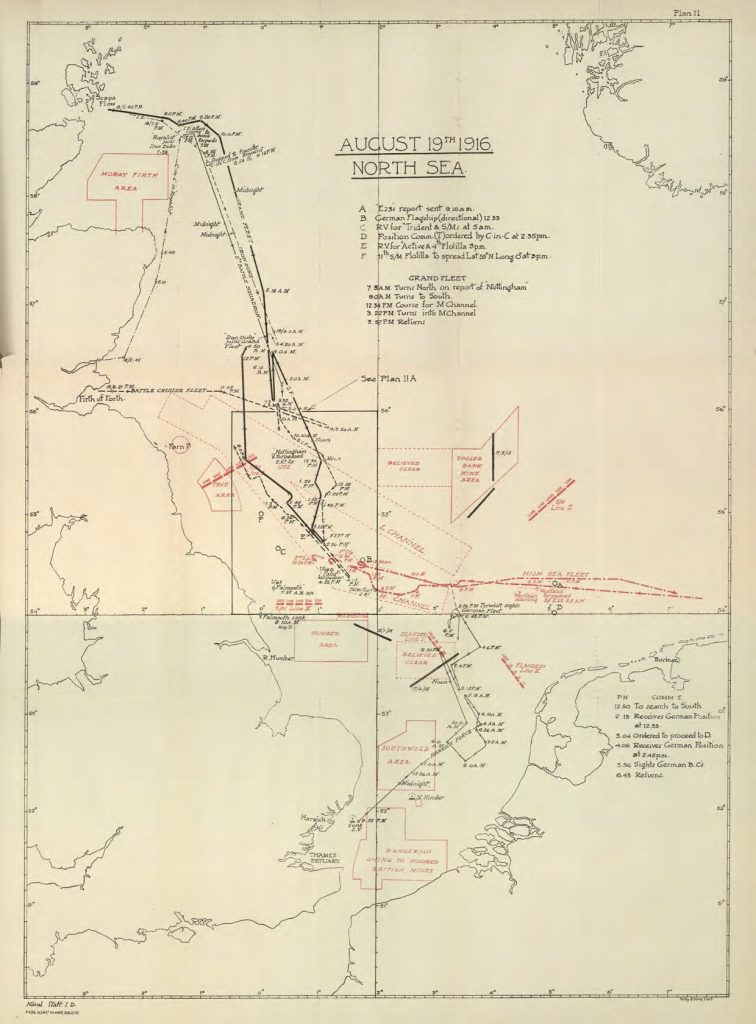

But the British had intercepted the German plan. Nottingham, operating with the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, steamed ahead of the main fleet to scout. In the early hours of 19 August, she and HMS Dublin (also ahead of the fleet) unknowingly entered a trap, a line of German submarines waiting to ambush any advance.

At 5:30am, Dublin sighted what appeared to be a small fishing boat. In reality, it was the sail of a German submarine U-52 manoeuvring into firing position. Twenty-four minutes later, two torpedoes slammed into Nottingham’s port side. Captain Charles Miller thought he’d struck a mine.

Below decks, the ship lost power. Fires and lights were extinguished. The crew gathered at stations in the dark. Minutes later, a third torpedo hit amidships. Water poured in. The ship settled heavily by the head and took on a 45-degree list to port, a posture later confirmed by ProjectXplore’s sonar imaging.

Still, the crew held formation. Guns continued to fire at a fleeting periscope. The ship’s wireless aerial had been destroyed, leaving her in radio silence. By the time nearby destroyers Penn and Oracle arrived, under torpedo fire themselves, Nottingham was sinking fast. She finally went under at 7:10am.

Sadly, 38 men were lost.

From charts to sonar

Despite repeated post-war searches, the wreck of Nottingham had never been found. Some had doubted her location had been recorded with accuracy. But in 2024, the ProjectXplore team began piecing together a new hypothesis.

The research team, including two native German speakers, analysed British naval charts, German U-boat logs, wreck databases, and hydrographic data. A breakthrough came in the detailed KTB (war diary) of U-52, which included a grid reference and a sketch of the attack. That single square, Quadrat 132 Y5, put the wreck in the open North Sea, well away from earlier search zones.

In late April this year (2025), sonar sweeps revealed the long narrow hull at 82 metres, with superstructure shadowing visible and funnel shapes matching the original plans. A few days later, the team returned with down-scan sonar and echo sounders to confirm height and position.

Then came the real test, diving the wreck itself.

Into the depths

From mid-July 2025, ten ProjectXplore deep sea divers (from the UK, Germany and Spain) equipped with underwater cameras began to document Nottingham.

Dropping a shot line into 80 metres of current-prone water was no small feat. “We were relying on everything we’d learned from April’s sonar pass,” said diver Joe Colls-Burnett.

The shot landed just aft of the mainmast. Divers descended into clear water and found themselves between two intact 6-inch Mk XII guns. The breeches were still sealed. Ammunition remained nearby, stowed and unused.

As the team fanned out, key features appeared: the embossed nameplate on the stern just beside the Captain’s day cabin; the wooden decking, still intact amidships; the engine telegraph fallen from the collapsed bridge; and the four funnels, just as war records described.

On the port side, divers found white plates stamped with Royal Navy blue crown emblems. The forward break in the hull, a massive tear in the deck near watertight bulkhead No. 40, aligned precisely with U-52’s torpedo report.

“The ship is in astonishing condition,” said diver Dominic Willis. “You’re not just looking at twisted wreckage. You’re seeing a working warship, frozen at the moment of loss.”

What ProjectXplore learned about Nottingham‘s sinking

ProjectXplore’s report includes extraordinary moments from the battle. Paymaster Lieutenant Davis, faced with orders to destroy sensitive documents, poured paraffin on the codebooks and lit them as the ship sank. “Having obtained permission, he simply walked into the water,” wrote Captain Miller.

Able Seaman Richard Bawden, just 21, leapt from Dublin’s cutter twice to haul drowning men from the sea. For his actions, he was awarded a Royal Humane Society Medal and promoted.

Rescue ships Penn and Oracle were themselves targeted by U-boats while picking up survivors. Unable to drop depth charges for fear of killing those in the water, they used evasive manoeuvres to dodge incoming torpedoes.

After surfacing hours later to examine lifeboats, the U-52’s crew found a naval rescue buoy labelled ‘HMS Nottingham’, and a ship’s cat curled in a drifting liferaft. Divers hope it lived out its days as a rat-catcher in a German harbour.

A preserved time capsule

More than 100 years later, HMS Nottingham now lies in remarkable condition, a silent sentinel on the seabed. Her survival owes much to the uniformity of the torpedo strikes, which concentrated damage forward of the bridge, and to the relative inaccessibility of her location.

Many other cruisers of her type, Birmingham, Lowestoft, Chester, were scrapped between the wars. Nottingham was the final unlocated loss from the ‘Town’-class series. Today, she remains the best-preserved of them all.

Her find is a poignant reminder of the risks faced by ordinary sailors. Some lost at the young age of 18 or 19. Others survived by swimming through burning oil or boarding lifeboats under torpedo attack. All served in one of the most dynamic theatres of naval warfare.

The site is now expected to receive protected status.