To secure the business, the quay punts would race each other out to sea, in all weathers and very often beyond the Lizard, to ‘seek’ incoming ships and offer their services. At one time there were up to 40 of them working in the port.

An essential characteristic was a mainmast short enough to clear the lowest yardarm of a heavily laden ship, and so the mainsail was gaff with no topsail. They were typically three-quarter decked for ease of handling cargo and, astonishingly considering the conditions in which they often found themselves, there is only one recorded instance of a foundering: Fear Not off the Lizard in 1900, with the loss of two hands.

By the early part of the 20th century, with considerably fewer ships calling into Falmouth and motor launches taking over, the days of the working quay punts were numbered. But their characteristics – seaworthy, suitable for shorthanded sailing, relatively fast, and with roomy hulls – were also highly desirable for cruising, and so not only were retired working boats easily converted to fulfil that new role, but new ones were commissioned to be built as yachts.

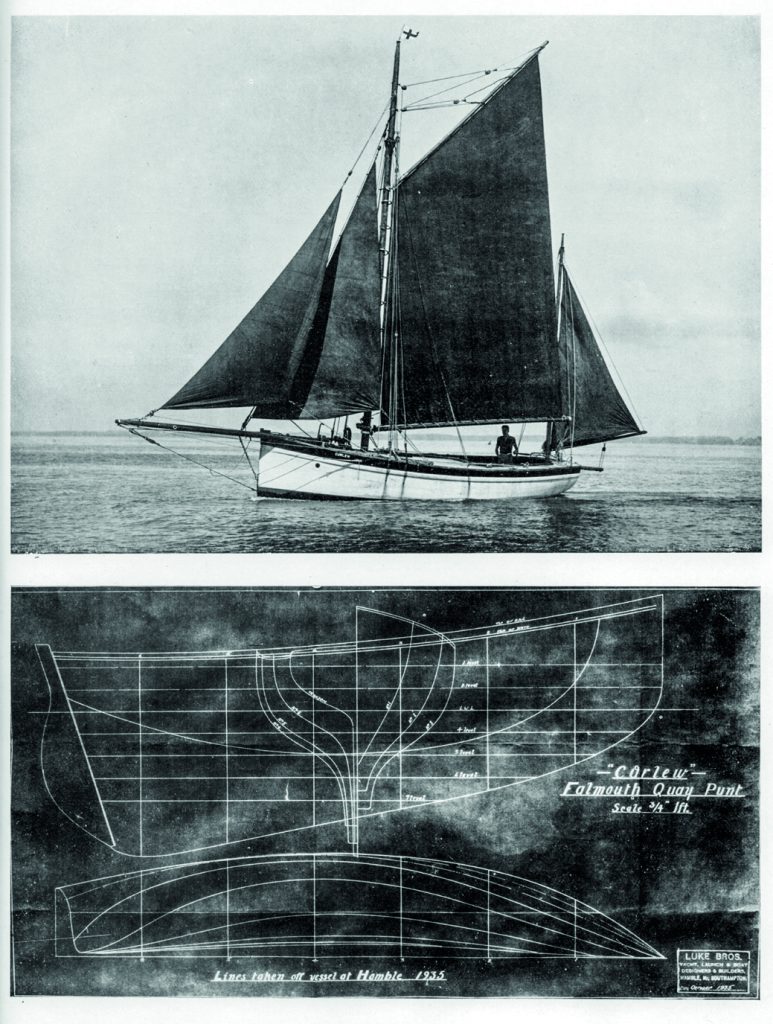

In 1912, Falmouth boatbuilder Thomas Jacket built a quay punt called Nada – with 1¼-inch pitch-pine planking on grown oak frames – which was later renamed Curlew. She must not, however, be confused with “the other Curlew” as Chris Harker, Nada/Curlew’s current owner, calls the one made famous by the cruising exploits of Tim and Pauline Carr. There is no definitive evidence to confirm whether Nada was originally a yacht or a working quay punt, but Chris is convinced that she was the latter.

Little is known of Nada’s early years, but it can be assumed that she earned her living out of Falmouth’s Custom House Quay along with the dwindling numbers of other working quay punts at that time. Around 1924 she was purchased by the artist Henry Scott Tuke who had previously owned two other quay punts: Cornish Girl and Lily. It is thought that he used Nada partly as a floating painting platform and also for fishing and for towing his various racing boats to regattas. Tuke last sailed Nada in September 1928, about six months before he died.

From 1934 – by which time her name had been changed to Curlew – her owner was Michael Tennant DSO a member of the Royal Yacht Squadron who kept her in Cowes until 1949. That was when he sold her to Arthur Such, a naval clerk who lived on board in Weymouth Harbour right up until his death – from a heart attack on board Curlew, according to his death certificate – in 1964.

Americans Miles Martin and his wife then bought her and fitted her out for worldwide voyaging but only got as far as Lisbon, probably due to Mrs Martin’s ill health. They left Curlew in the care of a local fisherman, but she soon fell into disrepair. In February 1969, following extensive flooding, the Tagus River where Curlew was moored, silted up. She then became stuck in the mud at low tide and was kept there by suction and filled with water when the tide rose. Throughout this time, Alf Henrik Amundsen, the Norwegian Consul in Lisbon, was in touch with Martin and made several offers to buy Curlew. Eventually, about a year after he paid to have her re-floated, Martin accepted Amundsen’s offer.

The Amundsen family – including four children – then spent several years using Curlew extensively, from Sesimbra and then Vilamoura and cruising as far south as Morocco. In 1974 there was a military coup in Portugal. Although it was bloodless – and became known as the Carnation Revolution, when soldiers placed carnations in the barrels of their guns – owning a yacht at that time was considered by many to be unacceptable, and a lot were burnt or ransacked, and so the Amundsens employed an Angolan ex-mercenary to live onboard Curlew to protect her and other boats they owned.

By 1980, the Amundsen children had grown up and moved to Norway, and so Curlew was sold to Joao Moreira Rato, a Portuguese Navy officer. During his ownership, fairly extensive structural work was carried out on her centreline by the naval dockyard. Then, in 1996, she returned to the UK by road after she was purchased by Devon architect Richard Carman and his wife, Sue. They, too, had four children, and the whole family cruised her throughout the West Country from various home ports.

It was in 2014 that Chris Harker heard that Curlew might be for sale due to Richard’s impending retirement and the now-grown-up children’s move away from home. Chris had sailed extensively on Bristol Channel Pilot Cutters over the previous 25 years. “I really like their working boat history and their gaff rigs,” he told me, “but it is important for me to be able to sail single-handed, and so a quay punt was a more practical and affordable proposition.” By February 2015, Curlew was Chris’s, and a couple of months later he brought her from near Saltash to Falmouth, where he put her on a mooring within sight of where she had been built over a century earlier. After sailing locally for a couple of years, he had her lifted out of the water at Freeman’s Wharf on the Penryn River for some much-needed work to begin, work that would be carried out by as many as sixteen different local boatbuilders and which would ultimately take two and a half years.

At that stage, Chris knew that the stem, most of the frames and much of the deck needed renewing. For additional strength, the grown oak frames were replaced by laminated oak. But it then became apparent that the original planks had so many fastening holes in them that they too would need to be replaced, and in the absence of sufficient quantities of pitch pine available in a reasonable timescale, it was decided to do so in larch.

The teak coachroof, which Chris thinks was fitted in the 1950s when she was converted from an open boat, was removed so that it could be refurbished in a workshop and then refitted. The beam shelf and most of the deck beams were replaced with recycled pitch pine, which came, directly or indirectly, from a china clay heated drying floor near St Austell. 18mm tongue-in-groove western red cedar was laid on top of them – for an authentic look in the cabin – followed by two layers of 12mm plywood sheathed in glass cloth and epoxy.

The internal joinery has been completely rebuilt in oiled sweet chestnut and white-painted tongue-and-groove. The layout includes a fo’c’s’le with good storage and a work bench which doubles as an occasional berth; an enclosed heads compartment; two settee/berths, the port one with a trotter box forward; a galley which extends aft under the bridge deck and has a two-burner meths stove and a sink; and a chart table which is also partly under the bridge deck.

The Lister Alpha 18hp twin-cylinder diesel, which was installed by Richard Carman in 1998, has been retained along with a 100-litre stainless steel fuel tank; a new 65-litre stainless steel water tank was installed; and the seacocks, plumbing, electronics, and wiring have all been renewed but kept to a minimum: the internal lighting, for instance, is provided by paraffin lamps.

The rig that came with the boat when Chris bought her has been retained. The age of the spars is unknown, but Chris thinks the main boom and gaff might be original.

One more piece of equipment that Chris would like to fit is a heating stove, and that is because he plans to go north. A long way north. “Ultimately I would like to take her to Norway, Svalbard and possibly Iceland and Greenland,” he told me. “But I think I will start by taking her up to Scotland for a couple of seasons, as that is where I grew up and did all my early sailing.” And from there he may take her to the Shetlands and Norway and then bring her back down the east coast. “A sort of three-year round-Britain trip taking the time to visit all the places that you wouldn’t go to otherwise,” he said. In the meantime, he is trying to develop a homemade self-steering system compatible with the protruding mizzen boom. “But you can leave the tiller for long periods, and she will sail herself,” he said.

Despite the frustrations of the project, Chris is happy that he now has a boat capable of taking on these ambitious challenges. “Curlew was originally built strong,” he said, “but the philosophy behind the project was to make her even stronger. I wanted to be confident in her wherever I take her, so I wanted everything done properly.”