Why sail a multihull solo in the first place?

There’s a certain freedom in casting off alone. No schedules to align. No watch rotations. Just you, your boat, and the sea. For many boaties, it’s the ultimate test of seamanship. But for catamaran sailors, it’s also about comfort, stability, and the ability to cruise longer and further in safety.

Catamarans have inherent advantages for solo sailors. They’re stable, fast, and spacious. Unlike monohulls, they don’t heel dramatically, making life onboard far more manageable when no one else is there to grab the frying pan or the winch handle. And if you’ve ever tried balancing a coffee pot on a rolling 35-footer in a stiff breeze, you’ll know just how important that is.

Still, sailing solo on a multihull isn’t without its own challenges. The wide beam makes docking and sail handling different. The extra canvas adds complexity. And yet, with the right mindset and gear, more sailors are choosing to take that step—from couples cruising to confident single-handers.

The sweet spot: finding the right cat for the job

Most solo cruisers agree that the ideal size for single-handed multihull sailing is between 10 and 14 metres (35 and 45 feet.) Large enough to handle offshore weather, small enough to be physically manageable without crew.

Also check out the new Lagoon 38, smaller again and designed for those who aspire to live and work on the water.

Modern production cats like the Lagoon 42 or Leopard 40 are often rigged for ease of handling. Lines are led aft to a single helm station, winches are electric, and autopilots are standard kit. Some even come with remote sail controls or touch-screen systems. These tech additions transform what once required three deckhands into a job for one.

Performance multihulls, like those from Outremer or HH, demand more from the sailor but reward with speed. They also require a more nuanced understanding of reefing and balance. If you know your boat and you’re willing to reef early, they can be just as safe—but they’re not for everyone.

When in doubt, err on the side of simplicity. Smaller boats with fewer systems are easier to master solo.

The Outremer 45 stands out as a model designed with solo sailors in mind. With its ergonomic helm layout, 360° visibility, and low boom height for easy sail access, it’s become something of a benchmark. Whether under tiller or autopilot, it offers both comfort and control for the confident cruiser.

Prep like your life depends on it, because it does

Solo sailing demands absolute forethought. Once you’re underway, everything takes longer, and emergencies are more serious.

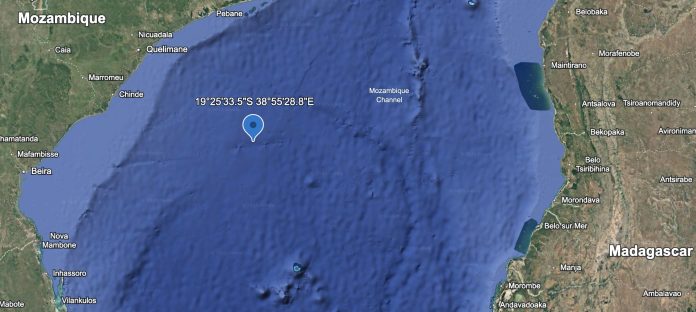

Route planning is the foundation. Know your harbours, hazards, and bolt-holes in advance. Plot waypoints on your GPS. Familiarise yourself with your route so you’re not flipping through guides when things get hairy. Practice reefing and sail changes at anchor. If your autopilot fails, do you have a backup plan?

Brieuc Maisonneuve, a seasoned sailor who recently delivered a Neel 43 trimaran from France to Venice, opted to sail the first leg solo. His take? “You have to know your boat before you leave. I made a route plan, checked every system, and carried AIS and a PLB. Once you’re alone offshore, there are no shortcuts.”

Heavy weather calls for conservative tactics. Trailing warps can reduce surfing and bow-diving. If you’re in a performance cat, use the windward daggerboard to pinch upwind. On a production cat without boards, running an engine can help hold your bow into the wind.

Most importantly: reef early. If you think it might be time to reef, it probably already was.

Safety systems: it starts with staying aboard

Falling overboard alone is a worst-case scenario. The solution? Don’t fall off. Solo sailors should always wear a tether in exposed conditions, and preferably a lifejacket equipped with AIS MOB beacon and PLB.

AIS beacons alert nearby vessels within 5 to 6 miles. PLBs trigger international rescue coordination. Together, they’re a belt-and-braces safety net—but neither replaces staying clipped in.

Autopilots are essential, but not infallible. Sleep near the helm (pilothouse setups make this easy). Use radar proximity alerts to wake you if vessels come close. Some sailors even set 20-minute timers overnight, nudging themselves awake for a quick horizon scan.

Fatigue is often the greatest threat. Keep a list of daily tasks posted in the cockpit or nav station. This military-inspired tip has saved solo sailors from forgetting critical steps during sleep-deprived passages.

Lessons from the water: the value of real experience

James Frederick, sailing solo in the Pacific, captured the highs and lows of the lifestyle. Battling a squall alone at night, soaked and exhausted, he questioned his decisions. But the next morning, under tradewind skies and gentle seas, he knew exactly why he chose this life.

Holly Martin, raised on boats and now cruising the Solomons solo aboard her Grinde 27, says: “Being at sea alone is a joy. I bought small and kept things simple. It’s more a mindset than an inconvenience.”

From Kiana Weltzien’s quiet communion with her Wharram catamaran in the Atlantic, to YouTubers testing tiller upgrades and tackling wind shifts alone, the stories echo the same truth: solo sailing is less about being alone, and more about being in control.

Your first solo trip: a test, not a trial

Before you point your bows at the horizon, take a solo day sail. Or better, go out with crew who promise to stay hands-off. Test reefing, tacking, anchoring. Find the blind spots, feel the load of halyards, learn how long things take.

Confidence doesn’t come from theory. It comes from experience. From making a night landfall with no engine. From crossing bars under sail. From recovering the drone while steering by autopilot.

Solo multihull sailing isn’t about heroics. It’s about self-reliance, smart systems, and knowing when to reef. And when you get it right, there’s nothing quite like the sound of the wake, the wind in your ears, and the quiet knowledge that you’ve got this.

Even if you’re the only one on board to say so.