Where confidence comes from

Most boaties remember the moment the sea stopped being an abstract idea and turned into something that demanded respect. The trainee watchkeepers aboard HMNZS Taupo had that experience in spades during their latest training phase.

The officers-in-training were out to join the Navy’s “Bravos” sea phase, where bookwork takes a back seat and the ship’s bridge becomes a working classroom. The plan was simple enough — coastal navigation, pilotage, and routine evolutions — until a Cook Strait weather system arrived with peak Wellington enthusiasm.

Gusts hit 50 knots, and the harbour entrance kicked up the sort of chop that makes even seasoned skippers watch the sets roll through.

Lieutenant Commander Toby Mara, Taupo’s Commanding Officer, wasn’t rattled. The ship’s design gives her the grunt to hold course when things get messy, and the atmosphere on the bridge remained steady.

“The conditions were exciting for the students, but the experienced members of the team were confident the ship could handle it,” he said.

For the trainees, it was a chance to put judgement ahead of theory. Wind, tide, sea state — all the factors they’d discussed in classrooms were suddenly very real, pressing against hull, wheel, and nerves. It’s the kind of experience no simulator can genuinely replicate.

Weather delays, but the work continues

The rough conditions forced Taupo to spend longer in port than intended, but this wasn’t downtime. Wellington Harbour offers its own style of training even on relatively settled days. With the wind gusting off the hills and sprinting across the water, the trainees worked through ship-handling exercises that demanded delicacy rather than bravado.

They practised turns, approaches, and station-keeping with a level of concentration that only a blustery harbour can insist on. For young watchkeepers, it was a reminder that seamanship is just as much about patience and precision as it is about handling open-water conditions.

Training alongside allies

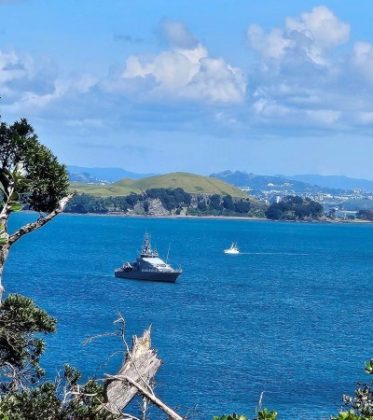

Earlier in the month, Taupo had been alongside ROKS Hansando, a Republic of Korea Navy training vessel visiting Auckland. The two ships carried out a simple escort evolution out of harbour, yet the value lay in the detail — shared manoeuvres, radio calls passed between languages, and the professionalism that keeps everything predictable even when navies operate differently.

“It’s such a great opportunity to work with another nation… our communications methods still stand up and we can conduct manoeuvres together,” Mara said.

For the trainees, it was a chance to see how the fundamentals of good seamanship cross borders.

Shifting coastline, shifting lessons

Across the year, Taupo has taken her trainees through a wide range of conditions: the busy Waitematā, the broken island terrain of the Motukawao Group, the Hauraki Gulf, the approaches to Northland, and exercises with HMNZS Canterbury. Each region forces different decisions and reinforces different instincts.

The return leg from Wellington added another chapter. The ship left harbour into Sea State 5 conditions with swell pushing hard on the beam, forcing a zig-zag course up the east coast. They tucked into Hawke Bay for shelter, then found calmer waters in Anaura Bay before rounding East Cape and continuing north.

Every one of those adjustments — sheltering, altering headings, reading conditions — sharpened the trainees’ understanding of what it means to handle a vessel responsibly.

Small ship, big responsibility

HMNZS Taupo might be the smallest ship in the Royal New Zealand Navy, but she carries a significant load when it comes to developing the fleet’s future officers. The Bravos sea phase is where young watchkeepers learn what can’t be taught on paper: how to weigh up risk, how to stay ahead of conditions instead of behind them, and how to move a ship safely through changing coastal environments.

By the end of the rotation, the trainees had seen more variety than many recreational skippers would experience in a season. Strong winds, confused swell, tight harbours, international interactions, and the need to adapt plans on the fly — each contributed to the sort of confidence that only comes from real experience.

For the Navy, that’s exactly the point. For the rest of us on the water, it’s a reminder that good seamanship isn’t theatrical — it’s built quietly, through days and conditions that leave a lasting impression.