A shift was noticed in Panama

Early this year, researchers tracking the eastern Pacific saw something odd. The Gulf of Panama’s dependable upwelling current failed to form. Usually, the region sees cold water pushed to the surface, lifting nutrients and sparking the plankton growth that underpins the local food web. Instead, the water stayed warm and still.

It was the first time since records began that the upwelling had not appeared. For scientists who work on climate and ocean circulation, the change raised obvious questions. Was this a short-term wobble or an early sign of something larger?

Understanding those patterns requires more than satellite data. Field measurements at sea remain the backbone of climate research, which is where a distinctive yacht enters the picture.

A purpose-built sailing research platform

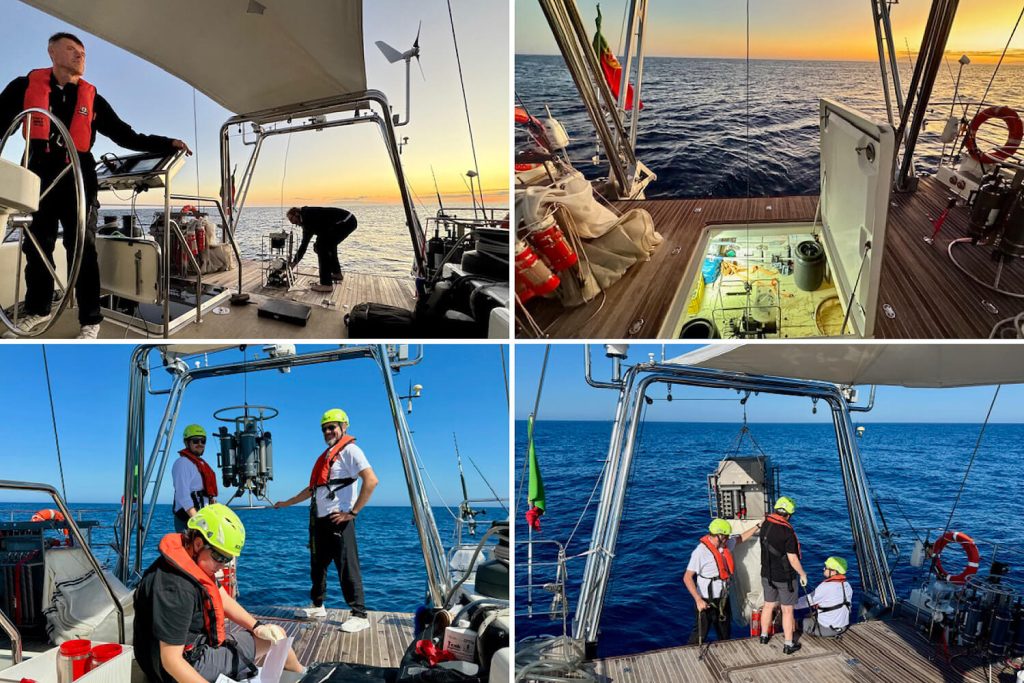

The 22 metre Eugen Seibold was commissioned by the Max Planck Society and built by YYachts within its custom programme: construction completed in 2018; launched and christened the same year; entered full service in late 2018. The design brief was unusual, calling for a long-range sailing vessel that could operate with a small crew and still carry enough equipment to support proper scientific work offshore.

The result is a yacht that looks like a clean-lined blue water cruiser yet carries the systems and working spaces normally found on far larger ships. Since entering service in 2018, Eugen Seibold has crossed the Pacific and Atlantic with two professional sailors and a rotation of five or six researchers on each leg. The boat’s composite hull keeps weight down, and its hybrid drive reduces noise and exhaust around sampling stations.

While the yacht is not large, the internal layout makes room for a compact clean laboratory, dry storage for scientific equipment and a working deck aft. These features allow the team to handle samples and instruments almost as soon as they come aboard.

Why El Niño demands direct measurement

El Niño remains one of the most influential climate patterns in the Pacific. When a pool of warm water builds north east of the Philippines, the trade winds weaken. Warm water then drifts east, altering weather in many regions and affecting marine life along vast stretches of coastline.

Although the broad outline is understood, scientists still have significant gaps to fill. They want clearer information about how different ocean layers behave, how local conditions feed into the wider system, and how warming seas may alter that rhythm in the future.

This is where Eugen Seibold offers something distinctive: steady, repeated sampling across open ocean stretches that research ships cannot always reach on tight schedules.

Because El Niño forms in the same eastern and central Pacific waters where Eugen Seibold collects data, her measurements help improve the global models that NIWA, MetService and NZ marine scientists rely on when forecasting our weather, ocean temperatures, fishing seasons and coastal conditions. Events that begin off Panama often influence New Zealand’s climate within months.

Working science from a sailing yacht

A deep water winch installed under the aft deck lowers sampling gear to 3,000 metres. A keel intake brings clean surface water into the yacht while underway. Once samples come aboard, they move into the small lab where temperature, salinity, fluorescence, oxygen levels and light penetration can be measured. Plankton communities are also recorded, giving the researchers a clear picture of how the biology shifts with changing conditions.

Climate scientist Dr Ralf Schiebel leads the programme.

“Our aim is to build a broad record of El Niño conditions,” he says. “We measure CO₂ in the atmosphere and in the ocean, and we take water at depth to see how everything connects.”

Because the yacht can travel slowly under sail or silent hybrid power, the team can gather cleaner samples than would be possible near the exhaust and vibration of large engines.

The missing upwelling and what it may signal

When Panama’s upwelling failed, Eugen Seibold was able to document how the water column changed. Instead of the usual cool layer rising from depth, the team found warm, stratified water with low nutrient levels. Plankton communities responded immediately.

Whether this event is linked to a developing El Niño or points to a change in regional circulation is now the subject of ongoing study. The samples collected on board are giving researchers a more detailed view of what actually took place, rather than relying solely on satellite temperature maps.

Changes in the Panama upwelling zone can signal shifts in the strength and timing of El Niño, which in turn may influence New Zealand’s summer rainfall, wind patterns, cyclone risk and marine conditions. For Kiwi boaters and fishers, understanding these upstream signals improves seasonal outlooks and coastal planning.

Feeding better climate forecasts

The measurements taken from Eugen Seibold feed into international modelling efforts. Oceanographers and climate scientists use them to refine predictions, particularly around how rising temperatures in the Pacific may influence future El Niño events.

Better forecasts have real-world value. Farmers, fishers, emergency planners and coastal communities all rely on accurate information. Long-term records from vessels like Eugen Seibold help improve those outlooks.

A long-running programme with patient goals

Interpreting the water, plankton and air samples collected on each voyage takes time. Researchers look for subtle relationships between chemical signals, biological responses and temperature changes across the water column. Those links help reveal how the system behaves and which indicators may give early warning of changes.

It will be several years before the current series of results is fully analysed, but the work already shows how valuable a modest-sized research yacht can be when built specifically for the job.

What lies ahead

The Pacific is warming, and long-standing patterns are becoming less predictable. Whether the Panama anomaly proves to be a one-off or an early hint of broader change will take time to confirm. For now, Eugen Seibold continues to range across the tropics and temperate zones, lowering sensors, collecting water and plankton, and helping scientists assemble a clearer picture of our changing ocean.

YYachts’ involvement is part of the vessel’s story, but the focus remains firmly on the science she supports. Purpose-built sailing research platforms remain few, and Eugen Seibold shows how effective they can be when designed with accuracy, endurance and simplicity of operation in mind.