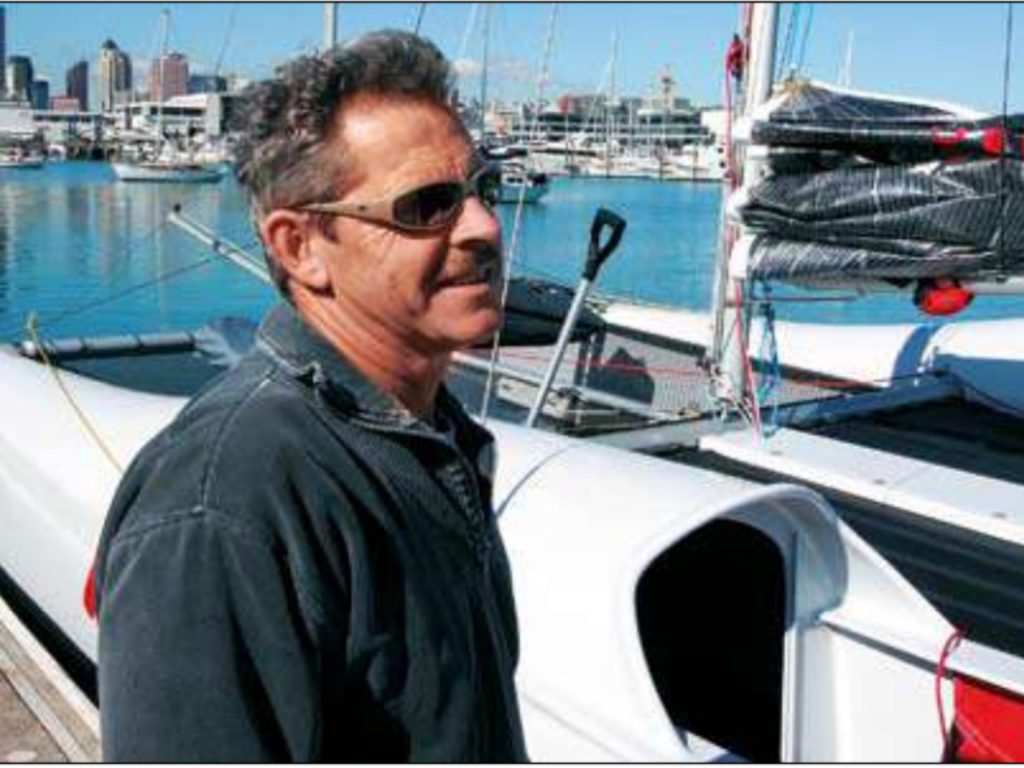

Introducing John Tetzlaff – full time sparmaker and part-time multihull designer/builder; by nature, quietly spoken and unassuming. Tetzlaff’s latest design and build effort, Attitude, makes an eloquent statement of what frugal amounts of time, money and 20 sheets of plywood can achieve.

Many Boating New Zealand readers will already have had brief encounters with John Tetzlaff through these pages, but Attitude is a particularly clear expression of his approach to boatbuilding.

Tetzlaff has built several compounded plywood multihulls for himself. His first effort was the Malcolm Tennant-designed, 9.7m racing cat, Illegal Alien. Then Tetzlaff designed a 9m cruising cat, Jungle Juice; then, a 9m racing cat, This Way Up; followed by a shift to tricycles with the 9m cruising trimaran, Repeat Offender.

Several years ago the New Zealand Multihull Yacht Club (NZMYC) promoted an 8.5m racing class. It was originally touted as a low cost way to attract sailors to multihulls, although some of the new boats launched for this class have ratcheted up $80,000-plus in materials, along with 2,000-plus labour hours.

For an 8.5m racing catamaran with barely camping accommodation, Tetzlaff considers these figures excessive. Believing in action instead of bar room chatter, he set out to build a competitive racing catamaran for under $25,000. Dockside with its smart grey paint, red signwriting and rounded shape, Attitude certainly belied that monetary limit.

Obviously, the budget precluded anything high tech regarding construction, and Attitude has been built from compounded plywood, also known as stressed or tortured plywood construction—see sidebar for a full description.

Attitude is development of Tetzlaff’s This Way Up, but a little fuller in the bows and a more flattened rocker. Up to the gunwales, Attitude is built from four millimetre gaboon plywood, sheathed with 300-gram boat cloth and epoxy. Two cedar stringers—one midway up the hull, the other at the gunwale—provide longitudinal stiffening. Decks and cabin tops are glass/foam/glass; the cockpit seating is plywood and foam.

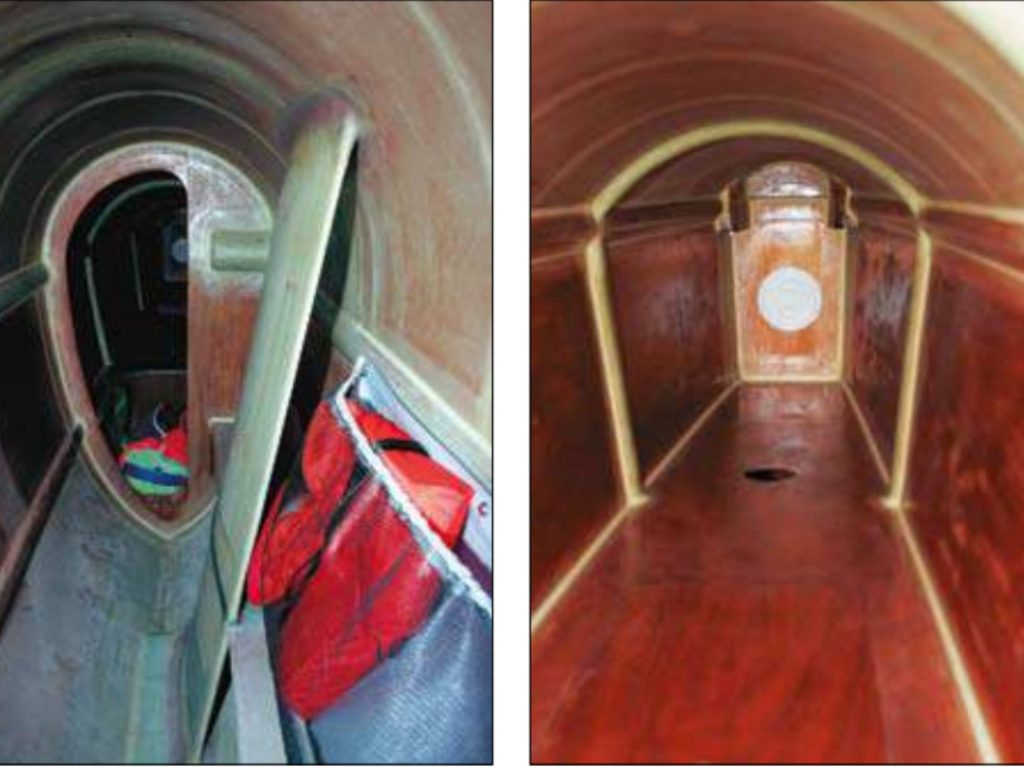

With no windows or sliding hatches, the interior is definitely claustrophobic, and although there are narrow bunks at either end of each hull, they are more to provide stiffening and watertight compartments than to provide sleeping berths. Cruising is spartan, but the odd weekend away shouldn’t present anything too masochistic.

The interior may have received scant attention, but the working areas have been intelligently thought through and executed. The cockpits provide a comfortable and secure location to drive the boat hard, with sheet and traveller controls close to hand on the inner cockpit shelf.

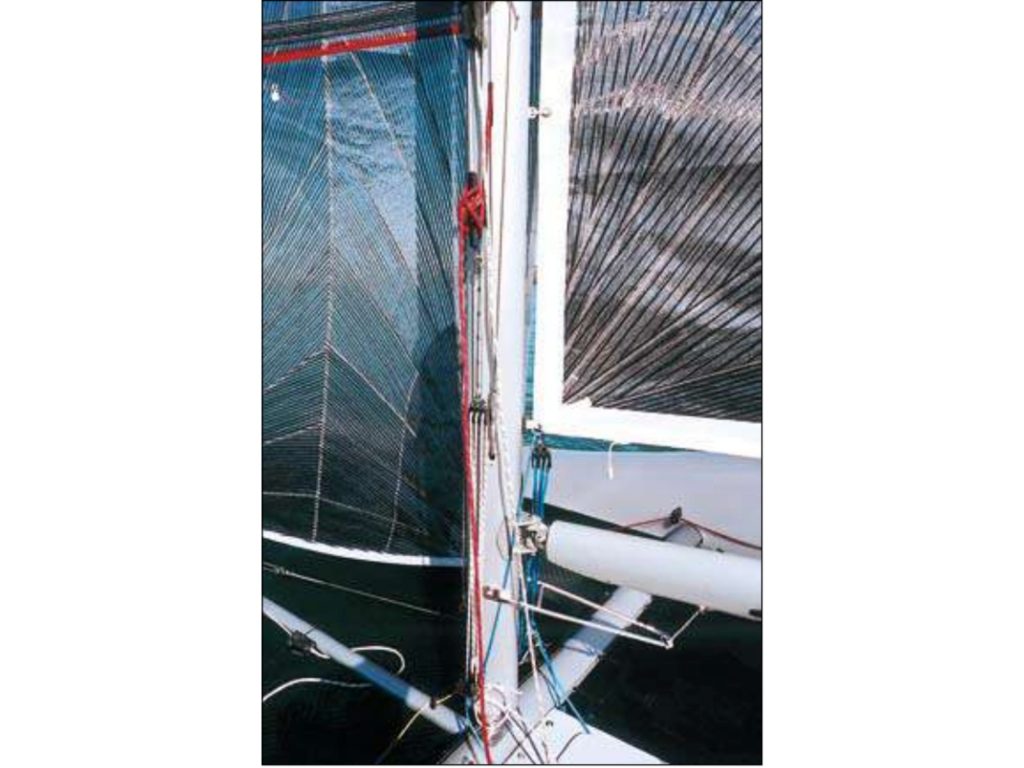

A central pod spanning main and rear beams divides the main trampoline into two, which helps tension it. Regular crewman Kim Admore of Rapture Designs built the trampolines and has done a nice job. The front trampoline is fishing net; the rear, Luminit, but as both are made from the same material, they should last roughly the same—seven years is average life expectancy.

As well as its obvious function of holding the outboard engine and anchor, the pod acts as a strut, preventing the main beam pumping fore and aft. It’s plywood, foam, glass and carbon, and built strong enough to support up to four-crew standing on it.

Rudders and daggerboards are GRP, produced from steel GBE/Turissimo moulds. The rudder housings are angled to place part of the rudder blades in front of the gudgeon axis to reduce steering effort. Tillers are courtesy of Marley 40mm plastic waste pipes, sheathed in carbon.

When fully deployed, cantilevered daggerboards can impose huge loads on their cases. On Attitude, these loads are contained by a plywood/foam/glass shelf midway down the daggerboard cases, right where the top of the daggerboard lies when fully down.

When Tetzlaff initially assembled Attitude in the shed, he set the beam at 5.5m, but this didn’t look right, and he settled on 5.2m. This relatively modest beam aids tacking and helps stiffen the boat diagonally—always a potential issue with aluminium-beamed cats. Although Attitude is not super light—Tetzlaff estimates sailing weight is around 950 kg—the boat is strong and feels solid underway. The bare hulls came out at 240kg each.

Tetzlaff built Attitude through his spar-making company, JT Spars, but made little attempt at trickery in the rig department. Based on a 155mm x 100mm extrusion, the rotating rig is kept in column with a single set of spreaders and twin diamonds, and held up by just three stays. There are no forward-facing jumpers, masthead runners, nor provision for a big jib or masthead screechers.

The sail wardrobe is deliberately small: a mainsail, self-tacking jib and secondhand gennaker—Tetzlaff believes a big sail wardrobe leads to far too much time deciding on and changing sails instead of sailing. He will add a storm jib.

The Doyle sails are built from GPL carbon, a durable fabric with performance and weight savings over Kevlar. Doyle’s manager Chris McMaster says Attitude’s sails were computer modelled on Doyle’s new Sailpack computer program, which was developed from wind tunnel testing for Volvo campaigns and benefits boats with large roach profiles.

There was a decided shortage of wind on for our sea trial, and we motored around for some time looking for a breeze. The Mercury eight-horsepower, two-stroke outboard is quiet, and has plenty of low down torque. With no instruments, speeds were estimates, but we reached what we felt to be hull speed on one-third throttle.

Compounded plywood constructionCompounded plywood construction is a fast, relatively low cost method to build light, slim hulls up to around 10m loa. It is a mixture of stitch-’n’-tape construction, combined with stressing or torturing plywood sheets into taking up compound curves; ie, a flat panel curved in more than one plane. The builder begins by scarfing sheets of plywood into two panels, the length and depth of the desired hull.An accurate,predetermined pattern of paper or ply is laid upon each panel, which is then marked and cut to shape. The two identical panels are stitched with copper wire or heavy duty monofilament fishing line along their respective keel lines, then spread apart like a book cover into a temporary jig. The jig establishes pre-determined angles along the length of the keel. Multiple layers of GRP/epoxy are then laid along the keel line, setting these angles. When the epoxy has hardened, the hull sides are progressively pulled together at the gunwale by multiple strapping or ties. This process continues until a deck jig can be dropped over the gunwales. Because the V-angle at the keel is fixed, pulling the gunwales together past that angle forces compound curves into the plywood hull sides. Compound curves from flat panels are impossible to form without force, hence, the multiple names for the method – compounded, stressed or tortured construction. Once the deck jig has been fitted, bulkheads, stringers, gunwales and other framing can be glued in, the bows glassed together and the transom fitted. These components lock the final hull shape and after the epoxy has hardened, the deck jig can be removed. There are some quirks with compounded plywood construction. The designer can draw a desired hull shape, but there are few guarantees it will be achieved in practice. Hull shape is dependent on the pattern accuracy, keel angle, plywood bendiness, plywood thickness and deck jig accuracy – all of which are difficult to predict on paper. The best test for whether a particular hull shape can be achieved is by building accurate scale models. There are size and shape constraints. Obviously, the distance between keel centreline and gunwale cannot exceed 1.2m – the width of a sheet of ply – unless another width of ply is scarfed or lapped on. Additionally, as plywood in excess of six-millimetre thickness becomes too stiff to compound, in practical terms this limits the method to hulls around 10m loa. Slim multihull or canoe hull shapes are easy to achieve with compounded plywood construction but monohulls are difficult unless it is a chined hull. Critics claim that compounding plywood imposes stress concentrations into the hull which may weaken it, increasing the chance of failure in an impact. Proponents counter this, saying their compounded craft are not designed to crash through reefs, buoys or other boats. Certainly, no one disputes properly designed compounded plywood boats are extremely stiff, and more than capable of withstanding normal sailing loads. Compounded plywood suits builders with good eyeball construction abilities and a sharp eye for fairness. Once a builder has got the technique right, he or she can produce pleasing shapes. However, builders who prefer the fairness of the hull to be the designer’s responsibility, or to work from accurate, dimensioned drawings, or CAD-generated full size patterns, may struggle with compounded plywood. For long, slim and light hulls, compounded plywood provides a relatively inexpensive, fast and exciting method of building boats, with excellent strength to weight ratios. |

After motoring down and back up the Waitemata, we finally found a localised 10-knot breeze just under the harbour bridge and quickly put Attitude through her paces before Hughie changed his mind. With such light conditions and perfectly flat water, sailing was more about impressions than a full-on sea trial.

However, this much is clear: Attitude is easy to sail and particularly easy to keep in the groove. The hull shape is quite buoyant forward for stability in strong winds and, in the light conditions, we picked up speed noticeably when we got some weight forward.

Bucking current trends, Tetzlaff is not a great believer in square-topped mainsails; he finds standard pinhead mains easier to trim. I had to agree—the Doyle sails gave a wide envelope to work in and required little tweaking.

Attitude was easy to helm and felt quite neutral upwind. However, there was some lee helm when on a hot angle under gennaker; the long prod obviously moves the centre of effort well forward. Tetzlaff believes he can tune out this characteristic; it is still early days in the sailing program.

The sailing controls are easily worked and low cost. The jib halyard cleats on a standard horn cleat mounted on a sliding track. A 12:1 rope purchase pulls the cleat downwards for tensioning the halyard which saves the cost of a winch, and is easier to use. There are two cockpit winches on each side and just one other winch, boom mounted, for the mainsail outhaul and reefing lines.

Tacking was a doodle, aided by the modest beam and the self-tacking jib. Changing cockpits when tacking was easier than on some cats, as the boom is set reasonably high.

Attitude has entered two races so far, with winds from 10 to 25 knots. Tetzlaff has found Attitude forgiving and easy to sail, and certainly not flighty. Considering the short work-up time, she is performing right on schedule in the NZMYC 8.5 class. In a recent race lasting 2.5 hours and in a broad range of wind conditions, she finished second on line, and third on handicap.

Attitude is a neat little boat. The small sail wardrobe and simple controls leave the crew free to concentrate on tactics and shifts.

Sure, there are lighter, higher tech and potentially faster catamarans available to buy or build, and for well-heeled sailors that’s fine. But anyone with finite budget, practical skills and a good eye, will find a JT 8.5 delivers the thrills without big bills. She’s simple to build, simple to sail and simple to race—that’s Attitude.

JT 8.5 Specifications

TYPE: racer

LOA: 8.5m

LWL: 8.3m

BOA: 5.2m

DRAFT: board down/up 1.7/0.3m

WEIGHT: 950kg

DISPLACEMENT: 1250kg

SAIL AREA: upwind 42m2

DESIGNER & BUILDER: John Tetzlaff

ENGINE: Mercury

HORSEPOWER: 8hp spars JT Spars

SAILS: Doyle Sails

TRAMPOLINES: Rapture Design