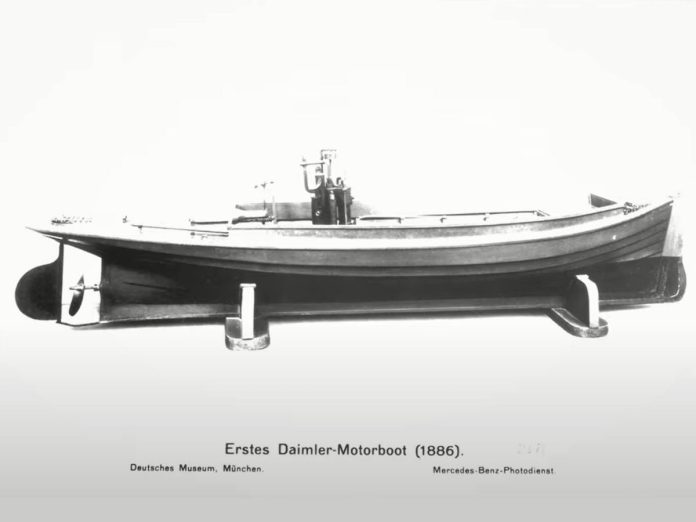

The spark: 1886 and the birth of the powerboat

The idea of a motorised boat was radical in 1886. But that year, on Germany’s River Neckar, boatbuilder Friedrich Lürssen fitted a six-metre timber hull with an experimental petrol engine built by Gottlieb Daimler.

Named Rems, this modest launch had a top speed of around 10km/h. But what it represented was far more powerful — the beginning of internal combustion at sea. Daimler’s engine wasn’t a one-off curiosity; it was a template. Over the next decade, petrol engines would proliferate across Europe’s rivers, lakes, and harbours.

Powerboating was born — but it wasn’t yet a sport.

Offshore powerboating: from timber testbeds to carbon speed machines

The 1890s: Speed, money, and mechanical mischief

By the 1890s, the early adopters were racing. Quietly at first, then loudly.

Wealthy industrialists and aristocrats worldwide — including in Australia and New Zealand — began installing petrol engines in their pleasure launches. In New Zealand, early motorboating took hold in Waitematā, Nelson, and as far south as Lyttelton. In Australia, the sport emerged in Sydney, Brisbane, and Perth. Across Europe, the Thames, Lake Geneva, and the French Riviera quickly became playgrounds for these new “auto boats,” or canots automobiles as the French called them.

Unofficial races sprang up. Boats lined up off docks for time trials or back-channel wagers. There were no trophies — just bragging rights. But reputations were forged in timber and steel.

Builders who made European history:

Thornycroft (UK): Naval roots, racing results

Originally naval shipbuilders, Thornycroft brought military-grade engineering to early motorboats. Their lightweight, efficient hulls were ahead of their time, drawing on years of experience with torpedo boats, those small, fast naval vessels designed to launch torpedoes at enemy ships to sink them. By the late 1890s, they were building sleek racing launches for private clients, many of which went on to compete in the first Harmsworth races.

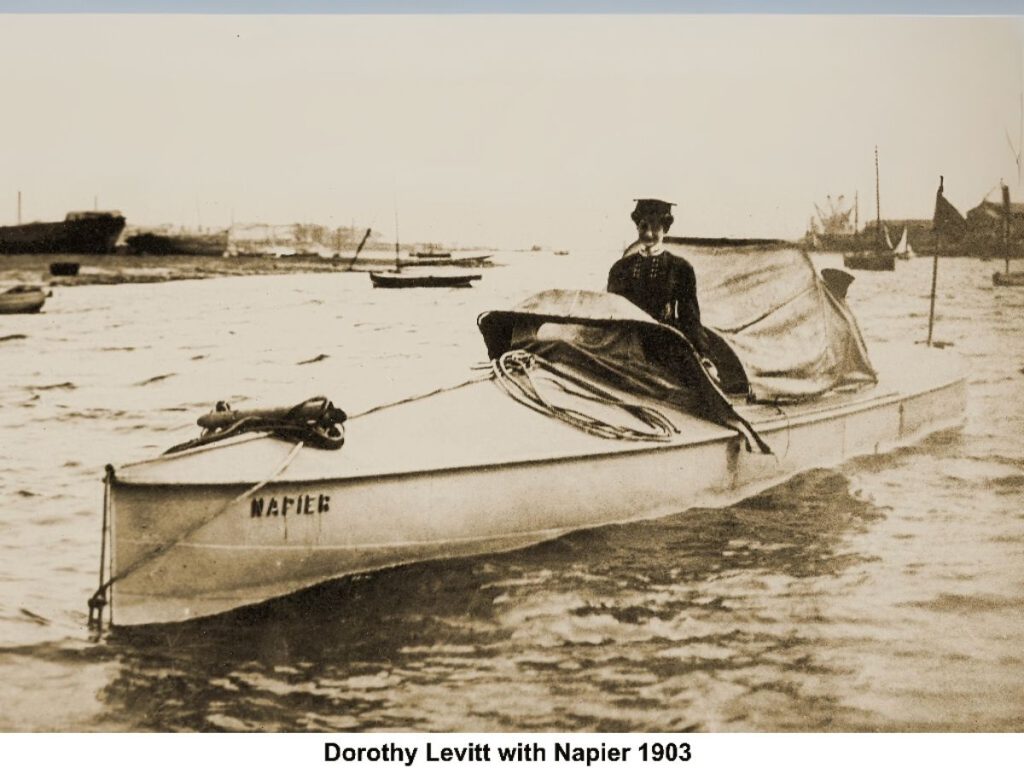

Napier (UK): From cars to powerboats

Known for fast cars and powerful engines, Napier quickly became a dominant force in early marine racing. Their purpose-built petrol engines set new standards for performance and reliability. Dorothy Levitt’s win in Napier I at the 1903 Harmsworth Trophy cemented their reputation as pioneers of speed — on both land and sea.

Canot Automobiles (France): French flair at speed

Blending elegance with engineering, Canot Automobiles built some of the most stylish and innovative early motorboats. Popular along the Riviera, their light, fast hulls and refined aesthetics won admiration — and races. With stepped designs and clean lines, they helped define the early French lead in European powerboating.

These boats rarely broke 20 knots. But they did break tradition.

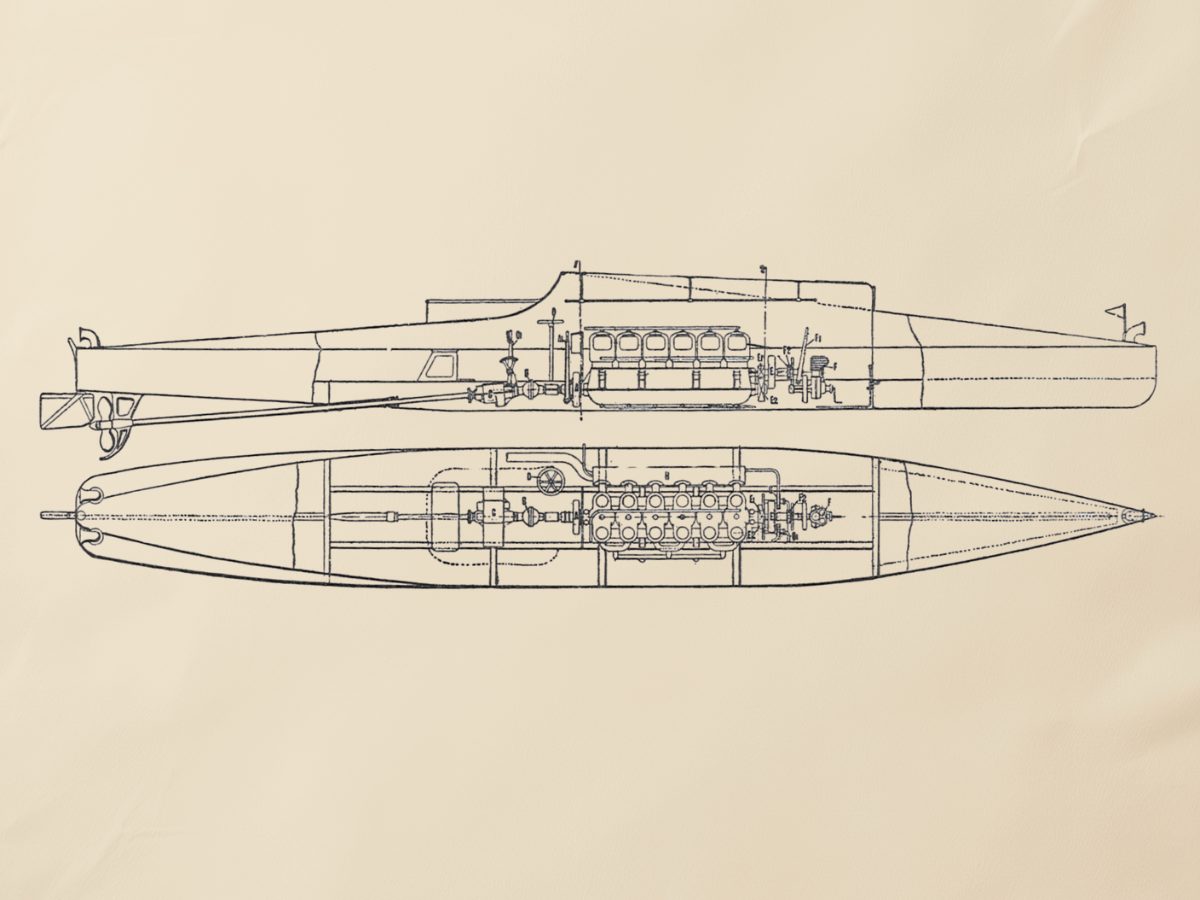

1898–1902: The speed wars escalate

At the turn of the century, when internal combustion engines were big, heavy brutes, it made perfect sense to mount them in displacement hulls. Their sharp, narrow bows cut cleanly through the water, pushing it aside, while the wake closed in quietly behind as though nothing had passed.

On England’s Lake Windermere, the Napier team thrashed their prototypes in timed sprints, often to the point of failure. Across Europe, engineering advances raised both performance and ambition. In Monte Carlo and Paris, high-society regattas embraced these noisy newcomers. Powerboat racing had emerged in the late 19th century, with early events in England, France, and Monaco. Hulls became sharper forward, fuller aft; engines more powerful; speeds climbing from 8 to 20 knots.

Yet there was still no single, unifying contest. No true international stage.

That would change in 1903 — thanks to one determined man.

Enter Alfred Harmsworth: journalism, nationalism, and the need for speed

Alfred Harmsworth — later Lord Northcliffe — wasn’t an engineer. He was a newspaper mogul. Owner of the Daily Mail, Harmsworth understood the value of spectacle. And he saw something potent in the noisy, smoky world of powerboats: a chance to stir national pride and sell newspapers.

He had already promoted the Gordon Bennett Cup for motorcars. Now he proposed something similar for boats:

- Races would be international.

- Each boat must be designed and built in the country it represented.

- The trophy would go to the nation, not the individual.

- And most importantly — it would take place in real water, not on lakes.

The Harmsworth Trophy was born.

1903 – The Harmsworth Trophy begins

The first race took place in Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland. It wasn’t offshore in the modern sense — the boats raced around a closed circuit in Cork Harbour — but it was a rougher, more demanding environment than the glassy lakes of Europe.

Boats from Britain and France competed, powered by cutting-edge petrol engines. Most were under 60 feet, built of wood or steel-reinforced timber. The race was marred by boats not starting, leaving only three entries.

Winner: Napier I, Selwyn Edge’s 40-foot 75hp Napier-powered steel speedboat fitted with a three-blade propeller, driven by England’s Dorothy Levitt — one of the first women in motorsport and a fearless pioneer. Levitt won at 19.3 mph, securing the trophy for Edge.

Levitt’s victory was as symbolic as it was strategic. Speed, technology, gender, and national pride collided in one boat — and the world took notice.

The Harmsworth Trophy was now the pinnacle of powerboat racing.

Dorothy Levitt: The Fastest Woman on Water |

| Dorothy Levitt was a fearless British pioneer of speed — the first British woman to race cars, the first woman to win a motorboat race, and the world’s first female holder of a water speed record. |

| In July 1903, Levitt won the inaugural Harmsworth Trophy — the first formal international powerboat race — driving a 75hp Napier speedboat to victory in Cork Harbour. She reached 19.3 mph, setting the first official water speed record. That same year, she raced and won at Cowes, was congratulated by King Edward VII aboard the Royal Yacht, and claimed the Gaston Menier Cup and Championship of the Seas in France. |

| Her boat racing career was short but trailblazing. Levitt wasn’t just fast — she was the public face of early marine speed. Sponsored by Selwyn Edge and Napier, she showed the world that women could master machines, command respect, and win. |

|

|

| Levitt later went on to break the women’s land speed record (90.88 mph in 1906), publish a motoring handbook for women, and inspire a generation of female drivers — all while dressed with Edwardian flair and accompanied by her dog, Dodo. |

| In the story of offshore powerboat racing, she remains a foundational figure — and one of its most audacious early champions. |

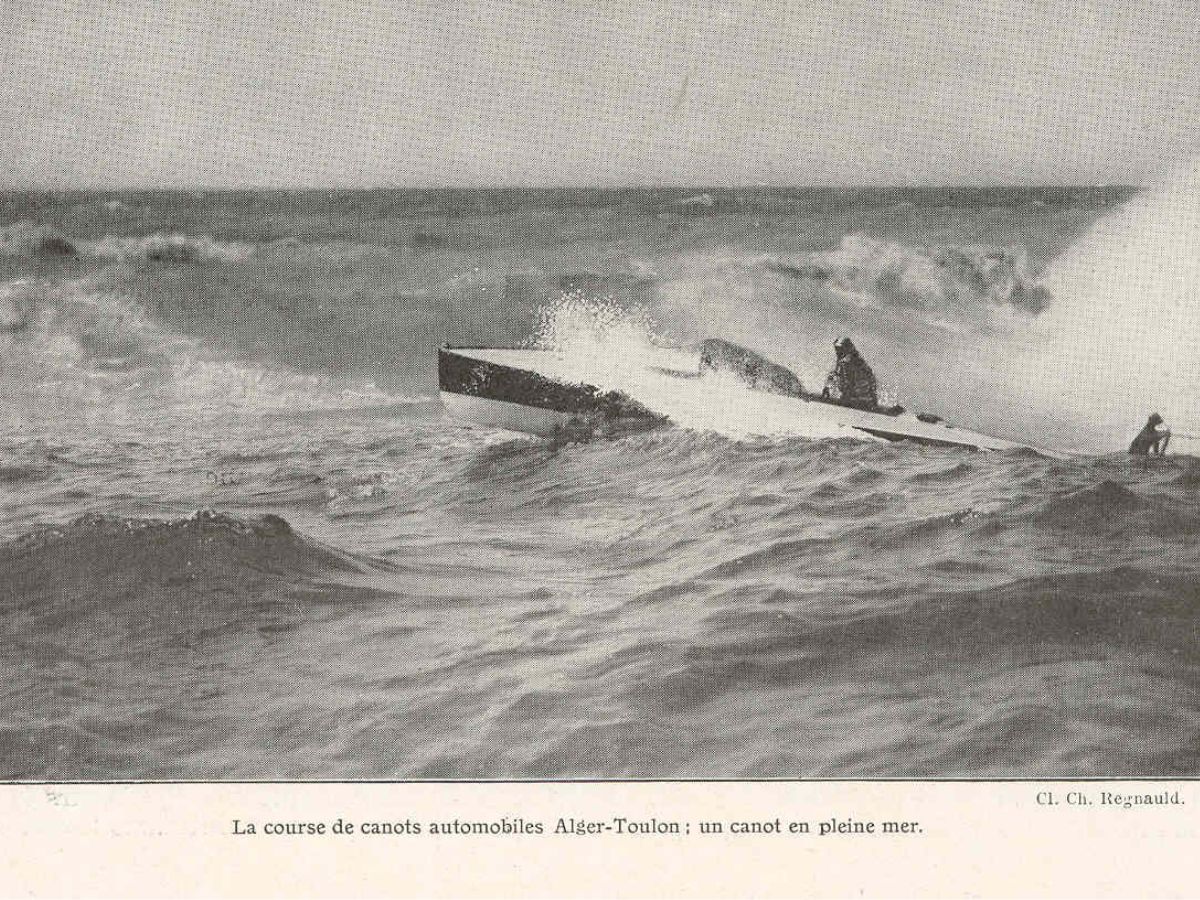

1904: The first true offshore race — Calais to Dover

If the 1903 Harmsworth Trophy marked the birth of offshore racing, the 1904 22-mile Calais to Dover contest was its coming of age. The English Channel, a notoriously turbulent stretch of water, proved the perfect proving ground.

As reported by The London Times (9 August 1904), the French boat Mercedes IV, powered by a 60-horsepower engine, completed the course in one hour and seven seconds to take first prize for fastest time in the racer category, with the English Napier Minor finishing second. The race was notable enough that, four days later, the Western Mail (Perth) carried its own brief account.

With wind, waves, and open-sea uncertainty replacing the calm predictability of harbour courses, offshore powerboating was no longer just a spectacle. It became a test of seakeeping, navigational judgement, and mechanical endurance — the defining traits of the sport we recognise today.

In many ways, the Calais–Dover race was the blueprint for events like:

- Raid Pavia-Venice: the world’s longest powerboat race, a challenging 414 kilometre (247 mile) event that has been held since 1929.

- Cowes–Torquay–Cowes: a legendary offshore powerboat race, 306 kilometre (200 mile) challenge that started in 1961, with boats racing non-stop from Cowes on the Isle of Wight to Torquay and back. The 2025 race is just around the corner.

- Key West Offshore Worlds: the pinnacle of professional offshore powerboat racing, held annually since 2004 in Key West, Florida, and is considered the “holy grail” of the sport.

A legacy of innovation

The transition from Rems in 1886 to Mercedes IV in 1904 was more than just a jump in speed. It was the shift from mechanical curiosity to marine sport. From wealthy hobbyists to international competition. From riverside antics to salt-spray battlefields. Offshore powerboat racing didn’t start on the ocean — but it got there fast.