A lifetime spent watching a fishery fade

For many people the Hauraki Gulf’s decline feels recent. For Barry Torkington, it has been unfolding for more than half a century. Barry grew up at Ti Point overlooking Omaha Bay, spending his early years on and around boats when the Hauraki Gulf was still full of life.

He remembers a coastline overflowing with crayfish, snapper, kahawai, trevally, parore, gurnard and rich shellfish beds. Those memories do not match today’s reality. That gap between then and now is the heart of his concern. Each generation accepts a depleted state as normal, slowly lowering expectations over time.

Who is Barry Torkington?

Barry is not simply a lifelong fisher with sharp observational memory. He is one of New Zealand’s most experienced voices in fisheries management.

He served as Chairman of the New Zealand Fisheries Symposium in 2016, has a deep background in commercial fishing and aquaculture, and spent many years as a director with Leigh Fisheries Ltd, specialising in quality assurance and innovation.

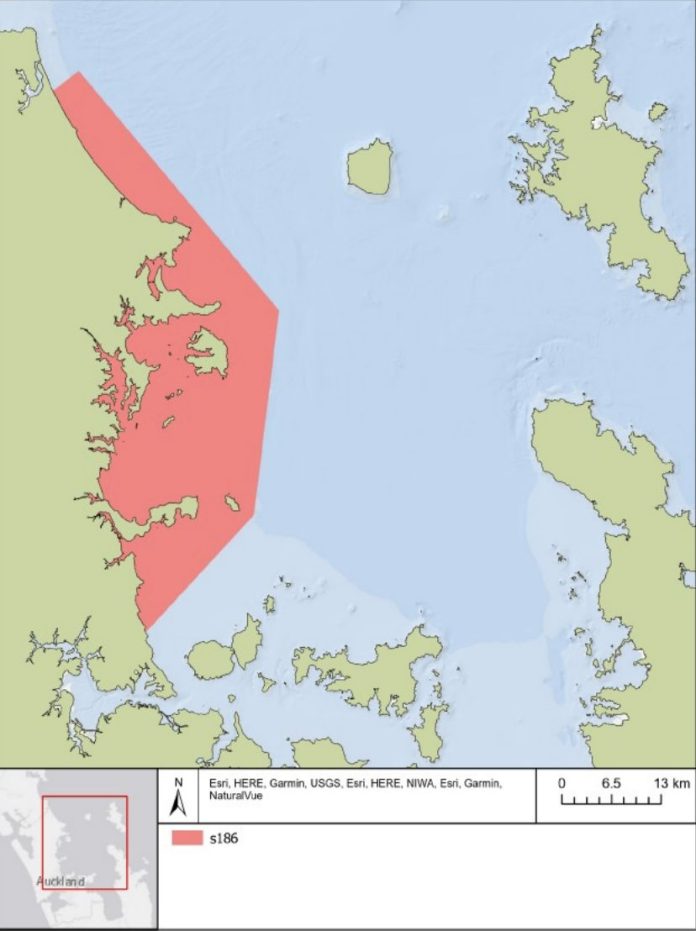

Barry has been closely involved in fisheries management for more than 30 years, contributing to two management plans for the country’s largest snapper fishery in Area 1 ((FMA 1) refers to the Auckland (East) and Kermadec marine area, covering the east coast of the North Island from North Cape to Cape Runaway, and extending out to the 200 nautical mile limit of the Exclusive Economic Zone.) Today he is an advisor to both the New Zealand Sport Fishing Council and LegaSea, offering science based, experience based insight that bridges the gap between commercial and recreational interests.

This depth of experience gives weight to his assessment of the Gulf.

When industrial methods arrived

Barry is clear about the turning point. The arrival of industrial trawling, seining and dredging in shallow inshore waters stripped habitats, stirred sediment, removed juvenile fish and wiped out benthic life within years.

Small scale inshore fishers were pushed aside by large vessels working high volume, high impact methods. The ecological cost fell on the fishery itself and on communities who depended on it.

Industrial fishing operations do not carry the cost of habitat destruction or biomass loss. Those costs are absorbed by the public. Close one area and the industrial fleet shifts to the next. The quota owners continue to profit, while the fishery grows weaker.

When the Quota Management System became a cage

Barry argues the QMS has locked in decline rather than reversing it. Independent fishers lease quota at high cost, carry all operational risk, and are constrained by rules designed around corporate needs rather than ecological goals.

Many fishers pay for quota before they leave the dock. Fuel, wages, maintenance and compliance sit on top. Quota owners collect rent without fishing, creating a system that rewards ownership and suppresses new ideas.

Despite the environmental cost, inshore fisheries contribute less than one percent of GDP.

Marine reserves cannot carry the weight

Barry supports protection tools but warns against seeing marine reserves and High Protection Areas as complete solutions.

Goat Island, protected for fifty years, is healthier than surrounding waters but still far below its original state. Reserves cannot rebuild a system that remains under stress outside their borders. Without real change in wider management, reserves risk becoming isolated pockets rather than engines of recovery.

COVID showed what is possible

One of the most surprising lessons came during the COVID lockdowns. Fish returned to harbours not simply because fishing stopped but because boat noise vanished. It showed how sensitive inshore species are to disturbance, and how quickly they respond when pressure eases.

What recovery requires

Barry’s recommendations are grounded in decades of experience:

- Rewrite the Fisheries Act and lift biomass targets

- Separate inshore and deepwater management

- Remove industrial harvest methods from inshore waters

- Restore shellfish beds, reefs and soft sediment habitats

- Reduce sedimentation and enforce land management rules

- Support small scale low impact commercial fishers

- Rebuild stocks before increasing catch

- Involve communities in fisheries management decisions

A message that cuts through

Barry’s central message is simple. The Hauraki Gulf did not reach this point by accident. The causes are known, the damage is measurable and the solutions are available.

Real recovery will take more than closures or symbolic zones. It requires structural reform and a commitment to rebuilding a fishery that future generations can recognise, not just read about.

This article is written with permission of Legasea, based on their podcast with Barry.