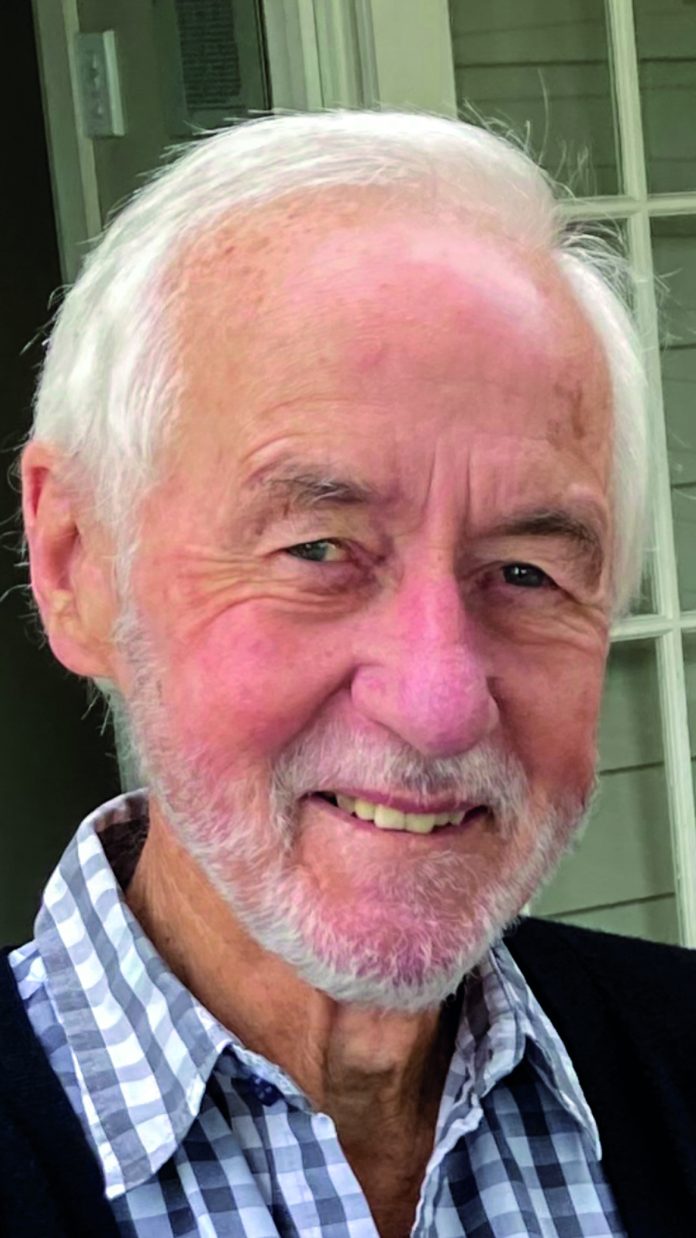

Many of Auckland’s boating community were saddened to hear that boatbuilder, surveyor and sailor Harry Pope had recently passed the bar. Fortunately, I’d previously spent time with Pope aboard his yacht Wolf with my tape recorder and this is his story. Story by John Macfarlane.

Harry Pope was born in Mt. Albert in 1929, the son of Devon man Harry Full, a Royal Navy matelot serving on HMS Diomede on the New Zealand station, based at Devonport Naval Base. Full had been a Seaman Boy aboard HMS Iron Duke at the Battle of Jutland in May 1916. Harry Pope’s mother Myrtle (nee Ladbrook) also had a seagoing association – her grandfather being master mariner and coastal skipper Capt. Robert Christian Lamb, who commanded the cutter Stag.

After the Fulls divorced, Myrtle remarried in 1937 and Harry took his stepfather’s surname of Pope. He was drawn to sailing from a very early age, joining the Point Chevalier Sailing Club aged nine in 1938. There he learned to sail a friend’s sailing dinghy, Twerp, which had a well-earned reputation for tenderness: “Everybody in Pt Chev [had] tipped out of it.”

The first yacht Pope actually owned was a one-off 3.6m sailing dinghy, which he paid for by doing a double paper round. He started labouring work on the waterfront at age 13, saving enough money by 1944 to sell his dinghy to buy the 18-footer Flash which he renamed Sea Wolf. The name came from Pope’s mistaken belief this was the name of Count von Luckner’s WWI commerce raider, actually Seeadler.

Sea Wolf III at the start of the 1951 Trans-Tasman race.

Two years later he sold Sea Wolf to buy the 22ft mullet boat Rewa, which he renamed Sea Wolf II and entered her in the 1946 and 1947 Auckland to Tauranga races. He then cruised the Northland coast taking on a number of odd jobs to pay his way. Pope eventually came across the Walter Bailey-designed 10m keeler Iris, which he and friend Bill Brierley bought with the intention of taking offshore.

In those days Pope didn’t have much boatbuilding experience and missed several latent defects resulting from an earlier rebuild of Iris. These repairs weren’t improved when Iris fell over when hauled out for a pre-sale inspection. Brierley and Pope decided to buy Iris anyway and spent nearly two years rebuilding her at Ken Low’s slip in Whangarei while living in a tarred tent alongside. One day Pope set the tent on fire while burning off paint, leaving the pair destitute.

Eventually the yacht was finished and renamed Sea Wolf III. After a shake-down cruise, the pair set sail for the Kermadec Islands intending to recreate Johnny Wray’s voyage. One hundred miles out, Brierly decided he didn’t like ocean walloping and the pair turned back. Pope bought Brierley out and instead entered Sea Wolf III in the 1951 Trans-Tasman race.

There were eight other entries but sadly Sea Wolf III finished last on line and handicap. However, considering the shoestring rebuild and that it was Pope’s first trip offshore, it was still a meritorious voyage.

Pope and his eight crew enjoying a drink following the 1966 Auckland to Suva race.

He sailed Sea Wolf III back to Auckland and got a job working for Shipbuilders. But due to the irascible foreman Oscar Brodeleau this didn’t work out so he left to join Chas Bailey & Sons, then operating out of Beaumont Street. Due to his age, Pope became an adult boatbuilding apprentice.

Bailey’s then had a big staff with separate crews for ferry maintenance, joinery, boatbuilding and shipwrighting. Apprentices would spend six months with each crew. There was another crew to work Bailey’s slipways, of which Pope would eventually become Slip Master. Bailey’s bigger slip could handle vessels up to 30m length and 300 tonnes weight. Apart from powered winches, much of the hauling out and moving of boats was done by hand using jacks, braces, wedges and greased planks.

Late in 1957 there was a big fire at Bailey’s and many staff were let go. Working conditions in the half-burnt yard were abysmal and future plans uncertain. In those days, the relationship between Bailey’s management and the workforce was testy. Boatbuilders rated fairly low on the totem pole and had to take what was handed out. Risking his job, Pope wrote a strongly worded letter to the management, which stimulated them to decide to properly rebuild the yard, this time with a few creature comforts such as showers. These were more than useful after some of the jobs such as scraping off antifouling or crawling around in tarred bilges.

However, there was little in the way of safety clothing, dust protection or even gloves for handling red and white lead. Safety processes were minimal and relied more on an individual’s sense of self-preservation. Guards on dangerous machinery were conspicuously absent and accidents such as fingers being chopped off with saws or getting caught in unguarded machinery weren’t uncommon. Additionally, apprentices were fair game for all manner of harsh or cruel jokes. It was a tough environment.

Wolf after launching in 1965.

“The characters around the waterfront were hard men.” In 1956 Pope began undertaking inspections for yachts intending to go offshore. This was a government initiative in response to the several boats that got into trouble during the 1956 Auckland to Suva race. The late Max Carter and Pope were the first two inspectors appointed. These were unpaid honorary positions,

“I got five pounds for 15-years’ work and never another cracker out of them,” said Pope.

Around this time he began building his own yacht after hours. He commissioned the late John Woollacott for a design based on his 11m Rambler design. Pope was on a tight budget and obtained much of the four-tons of lead for the keel by diving on wrecks in the weekends, but more about this later. He obtained the kauri from the Ponsonby reservoir which was being demolished at the time. Pope cut the kauri baulks up on Bailey’s shipsaw, then broke these down into the planking stock on the Shipbuilders bandsaw. The 10.4m lengths of kauri were then lashed to the side of Pope’s trusty Model A Ford and transported via the back roads to his parent’s house in Mt Albert late at night.

“I never got picked up, not once. I thought if Johnny Wray can do it, so can I.”

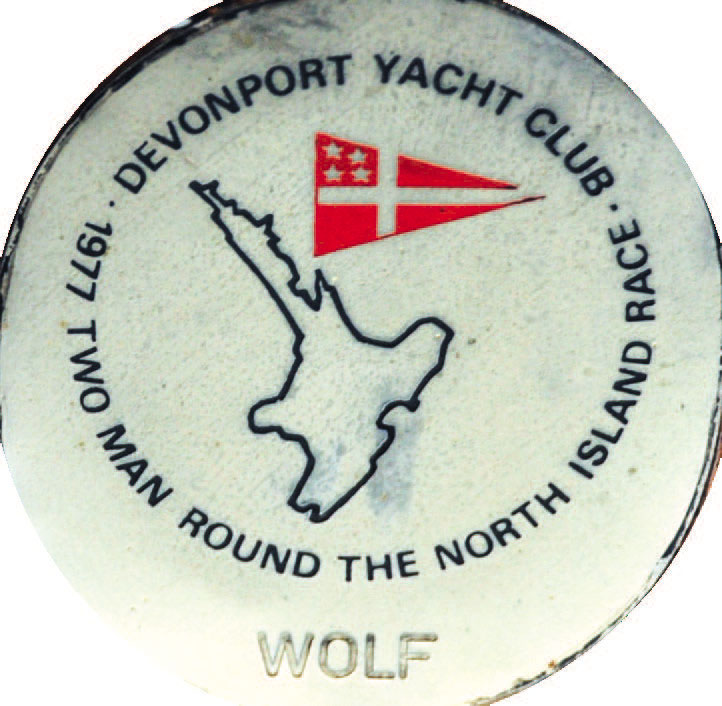

Wolf was launched in 1965 and Pope entered her in the 1966 Auckland to Suva race. Due to light winds and the lack of working up time, Wolf didn’t do well in that race, but in the 1973 race she came second in her division and third overall. Several years later, in 1977, he and Ernie Seagar entered Wolf in the Around the North Island Race. “That was the best race I’ve ever sailed in.”

Wolf’s memorial plaque for the 1977 Two Man Round North Island Race.

Wolf’s memorial plaque for the 1977 Two Man Round North Island Race.

Pope also crewed for a number of other yachts in offshore events including the 1951-2 Whangarei to Hobart Race and Hobart to Auckland races in Gesture, the 1956 Auckland to Suva Race in Ranganui, the 1961 Auckland to Sydney Race in Jeanette, the Whangarei to Noumea Race in Princess Persephone, and the 1980 Tauranga to Vanuatu Race in Northerner.

By 1970 Pope was becoming disenchanted at Bailey’s and felt his career wasn’t advancing. He asked for changes but was fobbed off. So, he left Bailey’s and struck out on his own as Pope’s Marine Surveys, which over the next 20 years would see him surveying thousands of boats from pleasure boats to commercial ships. Besides his surveying, Pope also undertook diving, salvage, yacht deliveries, brokerage and marine consultancy.

Pope began diving in 1958, when he, Gibby Gordon and Jack Owen began experimenting with home-made diving gear cobbled together from primitive on-demand valves, carbonic ice bottles and hoses. The trio experimented in shallow waters off the Bailey slipway and local beaches. The late Les Subritsky gave them valuable advice on the proper gear and safety procedures. Pope became a professional diver working such projects as installing the Whakatane pipeline and repairing the Arapuni dam, as well as many salvaging operations including the Moana Isles, Onewa, Northerner, Hazel Repton, Recovery and Sheila II.

One of the more interesting salvage projects was salvaging the 16m Northerner, which sank following an argument with Bollons Rock in the Tiri Channel. When Pope located her in 27m of water, Northerner had settled upright on the bottom.

“She was just like a ghost ship with her sails setting in the current. Someone would’ve paid moonbeams for a photo of her like that.”

Wolf’s registration number

After Pope removed her mast, Northerner was lifted to the surface, had her holes patched, was pumped out and then towed back to Auckland to be fully repaired by her original builder, the late Max Carter. Northerner’s now owned by Mike Webster and is regularly seen around Auckland.

Besides salvage jobs, Pope carried out countless underwater maintenance jobs on ships and ferries. But his bread and butter business was surveying thousands of boats and ships. Besides pre-purchase inspections, Pope was called upon for valuations, repair assessments and all the many tricky situations needing an impartial, expert eye. He also helped newcomers find the right boat. For example, he helped the late David Taggart buy Vega which later was used for a number of protest voyages against French nuclear testing in the Pacific.

Another income source for Pope was yacht deliveries, which he began in 1951 by helping delivery the 14.6m schooner Lady Sterling from Suva to Auckland. He also delivered the 10m launch Break of Day and the 9m launch Dove II from Auckland to New Hebrides in separate voyages and the 15.2m launch Ma Cherie from Auckland to Fiji.

He undertook countless coastal deliveries as well, including the well-known yachts Rainbow from Wellington to Auckland and Cotton Blossom from Auckland to Wellington. While Pope successfully delivered all his boats, a number of them were elderly and he encountered all manner of issues over the years – missing equipment, engine breakdowns, leaking seams and windows, inexperienced owners, drunken crew and bad weather.

Wolf at the start of the 1966 Auckland to Suva race.

Pope officially retired in 1991 but continued his keen interest in boating matters. During the early 2000s he started writing a few notes about his life for his grandchildren, which gradually grew into his book, Adventures of a Pope at Sea published in 2016.

“You don’t realise how much you’ve done [in your life] until you write it down. My memory’s pretty good – for an old bastard – but the more I wrote down, the more I remembered.”

Pope showed me over the strongly-built Wolf several years ago and he sold her a couple of years later. Pope passed away in July this year, being survived by his wife Barbara, children Susan and Jeffery, and grandchildren Jorden and Samuel.

One of the last things Pope said to me onboard Wolf was “I’ve lived my dreams and not many can say that.”

Sail on Harry Pope. BNZ

PHOTOS COURTESY HARRY POPE AND JOHN MACFARLANE

ADDITIONAL RESEARCH COURTESY HAROLD KIDD