From turbines to timber: tracing the roots of offshore power

In its prime, Miss GEICO was the most feared name in offshore powerboat racing. A 50-foot Mystic catamaran powered by twin Lycoming T-53 turbine engines, it tore across open water at speeds over 210 mph (340 km/h). Built from carbon fibre, Kevlar, and S-glass, the boat combined high-tech aerospace materials with over 4,200 horsepower of raw thrust.

Miss GEICO dominated races, broke records, and grabbed headlines across the world. But it didn’t begin there — not even close.

Almost a century earlier, on a quiet German river, a different kind of pioneer launched a very different boat. Just six metres long and made of timber, this craft wasn’t chasing records. It was chasing a question: Could a small engine drive a boat safely and reliably across water?

The year was 1886. The boat was Rems. What it proved would forever change the future of boating — not just offshore racing, but every engine-powered craft to follow.

A world before power: oars, sails, steam — and a shifting world

In the 1880s, most small craft were human-powered. Rowing boats, skiffs, and small sail launches dominated inland and coastal waters. Steam propulsion existed, but it was heavy, costly, and hazardous — requiring licensed operators and generating pressure few recreational boaters wanted to deal with.

Globally, the world was on the cusp of profound change. The Second Industrial Revolution was in full swing, electrification was spreading through cities, and combustion engines were starting to show up in road vehicles and factories. Germany, newly unified and industrialising rapidly, was a hub of technical innovation and growing economic strength. Political tensions across Europe were rising, but it was also a time of national pride and engineering optimism. For inventors like Daimler, the question wasn’t just whether an engine could work — it was how that engine could transform life itself.

Some experimental naphtha-powered launches had emerged — running on volatile hydrocarbon fuel instead of steam — but they were dangerous, finicky, and soon eclipsed by safer petrol engines like Daimler’s. In short, the small boat world was still waiting for a practical propulsion breakthrough. And that’s where two visionaries stepped in.

Lürssen’s timber boats: precision, not power

Friedrich Lürssen founded his shipyard in Aumund, a riverside village near Bremen in northern Germany, in 1875 — but not entirely by choice. His father, Lüder Lürssen, was a respected boatbuilder who insisted that if Friedrich wanted to pursue boatbuilding, he had to do it independently. So, at the age of 24, Friedrich opened a small workshop with a single assistant and quickly gained a reputation for excellence.

He specialised in lightweight wooden boats: rowing skiffs, small ferries, and fast sport launches built for performance under oar or sail. Lürssen initially only built racing rowboats for Bremen oarsmen, but demand quickly spread across Germany. His boats became renowned not only for their elegant lines, but for their precision workmanship, quality construction, and impressive speed. Thanks to their lightweight build, Lürssen boats regularly placed well in regattas and were praised for their competitive performance. They were, in essence, the perfect candidate for something more daring.

That small workshop would eventually grow into one of the world’s most prestigious shipyards. Today, Lürssen is known globally for building some of the largest and most luxurious superyachts ever made, including vessels like the 180-metre Azzam — the world’s longest private yacht — and Dilbar, the largest diesel-electric system by gross tonnage at 156 metres.

But it all began with timber, hand tools, and a quiet push from a father who believed success had to be earned.

Enter Rems: the world’s first motor launch

Gottlieb Daimler was a creative and restless engineer — a man driven not only by precision but by possibility. Born in 1834, he apprenticed as a gunsmith before studying mechanical engineering at Stuttgart Polytechnic. His career took him through France and Britain before landing him at Gasmotorenfabrik Deutz in 1872, where he worked closely with Nikolaus Otto, the pioneer of the four-stroke engine. But Daimler had grander visions.

By the early 1880s, disagreements over direction led him to leave and set up an experimental workshop in the garden of his Cannstatt villa. There, with Wilhelm Maybach, he developed a small, high-speed petrol engine with hot-tube ignition — light enough to be applied across transport modes: road, rail, air, and water.

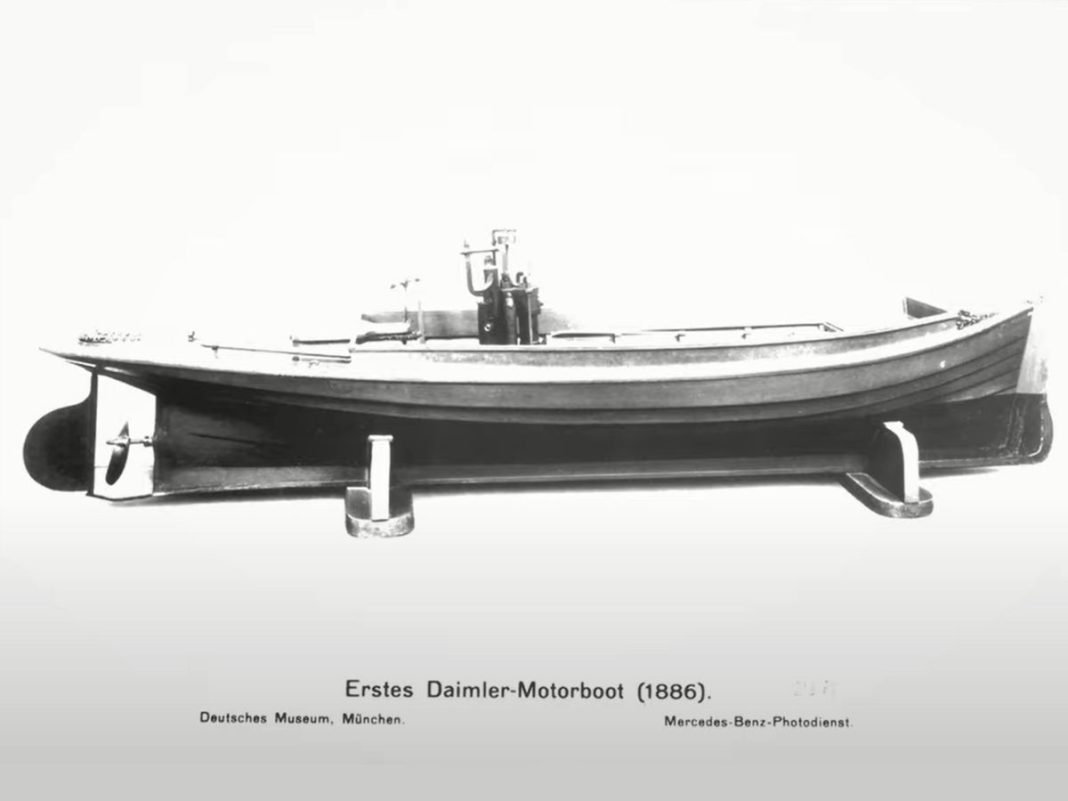

In 1886, Daimler commissioned Lürssen to build a boat to test this engine on water — the most challenging of all. Daimler was determined to prove that his lightweight internal combustion engine could power more than just land vehicles — he believed it had the potential to revolutionise all forms of transport, including on water. A successful marine trial would demonstrate the engine’s versatility and open doors to a broader market for his invention. The result was Rems — a six-metre timber launch, purpose-built for the world’s first successful marine trial of an internal combustion engine. Steering was via a simple transom-mounted rudder, controlled by a tiller. The boat was launched on the River Neckar near Cannstatt — a sheltered stretch of river ideal for Daimler’s revolutionary trial.

The hull was clinker-built using lightweight timber, shaped with Lürssen’s trademark precision. The design included a fine entry, modest beam, and gently rising sheerline to keep spray down and improve tracking. Fastenings were likely copper rivets, and joints were sealed with marine glue — a light but robust construction ideal for calm inland waters.

It was an odd-looking thing by today’s standards—6 metres long, 60 kilograms of engine clattering away at 700 rpm, producing a mighty 1.5 horsepower. Locals were sceptical. Some reportedly shouted that “the devil himself must be aboard” when they first saw it moving without sails or oars. But Lürssen had changed boating forever.

So revolutionary, in fact, that Daimler disguised the engine as “electric” to avoid alarming locals who feared explosions.

What Rems proved

That quiet river trial succeeded. Rems motored under its own power. It proved, for the first time, that a lightweight petrol engine could reliably propel a watercraft. The world’s first motorboat had arrived.

Rems was the testbed that launched an entire industry: engine-driven launches, powered pleasureboats, working vessels, and eventually, raceboats. Offshore powerboating hadn’t been invented yet — but the idea that speed, distance, and freedom could be powered by petrol? That began here.

The legacy: from 1.5hp to over 210mph

Decades later, offshore powerboating became its own spectacle. Endurance challenges like the 1956 Miami–Nassau race pushed hulls and engines to their limits. By the 2000s, turbine-powered catamarans dominated the scene — none more iconic than Miss GEICO.

Originally founded by John Haggin, and later operated by a team including Marc Granet and Scotty Begovich, Miss GEICO became one of the fastest and most successful offshore powerboats in history. One of its most formidable versions, a 50-foot Mystic catamaran, was powered by twin Lycoming T-53 turbine engines producing over 4,200 horsepower combined. It reached speeds exceeding 210 mph (340 km/h) — a blistering pace over open water.

The boat’s hull was constructed from carbon fibre, Kevlar, and S-glass — materials, then, at the cutting edge of marine engineering. During its dominant run, Miss GEICO secured multiple world championships, broke offshore speed records, and even appeared in mainstream media and documentaries. Though officially retired in 2021, the legacy of Miss GEICO lives on as the ultimate fusion of technology, teamwork, and velocity.

It was, in many ways, the opposite of Rems. But also its direct descendant. Both set out to see what might happen when you push past convention. Now the question is, how fast, how far, and how daring can one boat go?