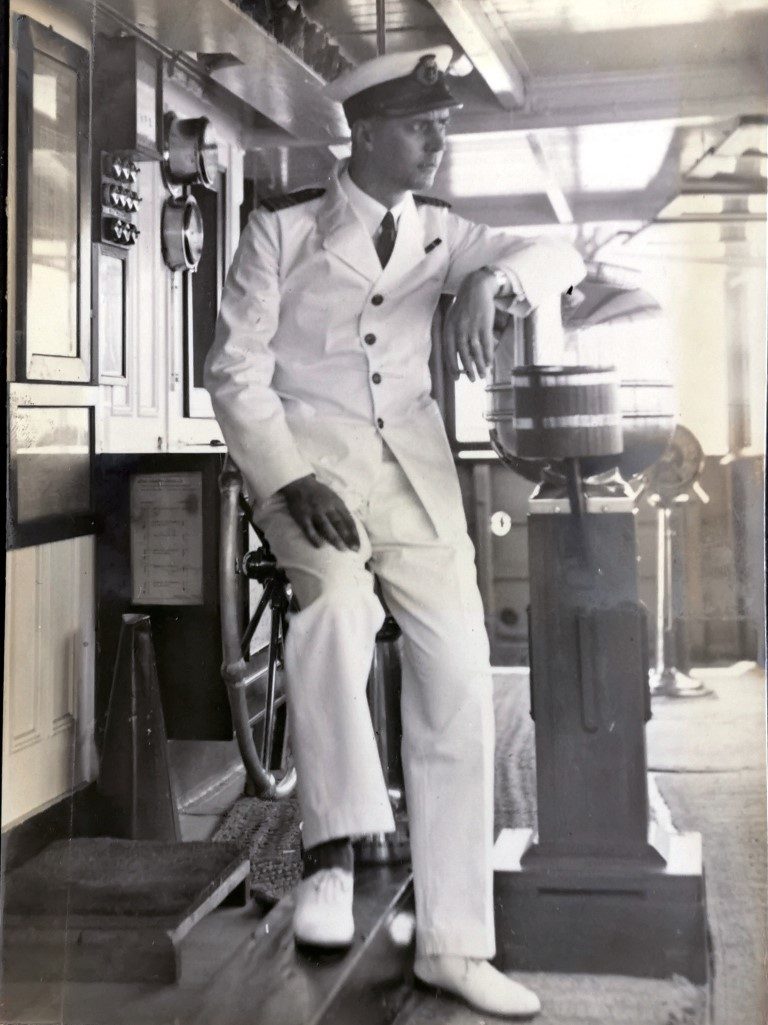

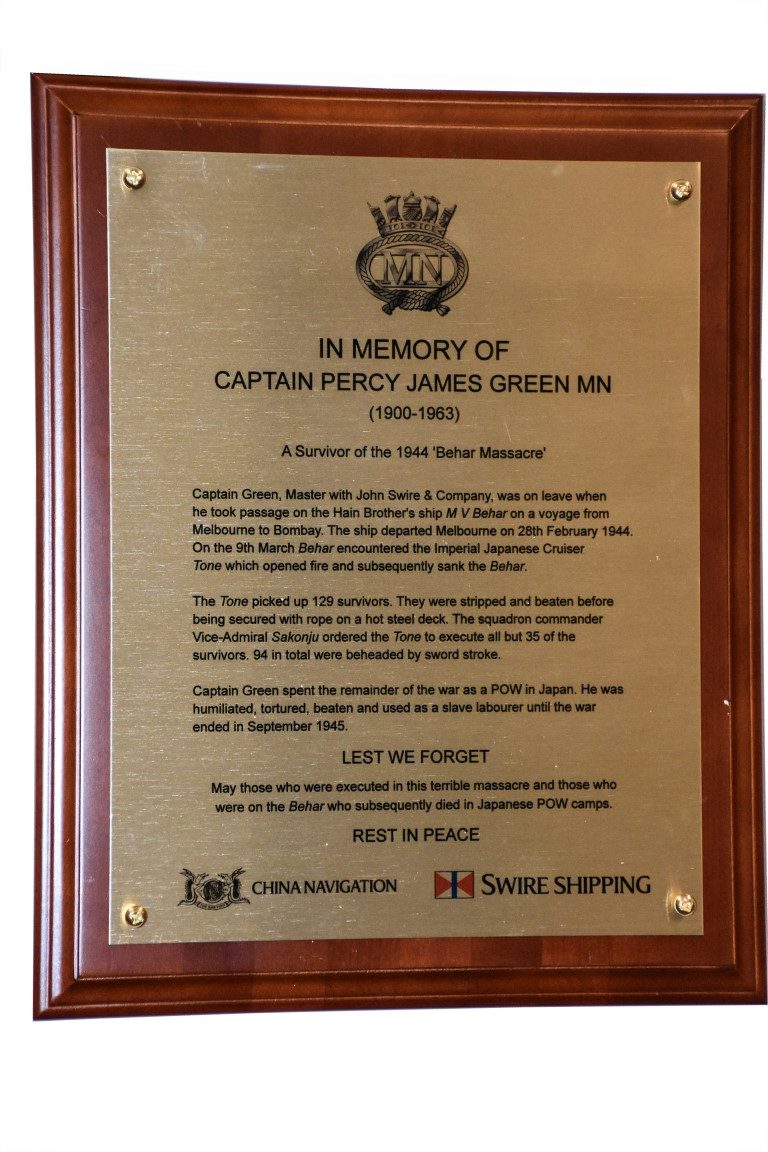

At the city’s International Seafarers Centre in April this year, Auckland music teacher Dora Green unveiled a commemorative plaque to her father. Percy James Green was a British Merchant Navy Master who in 1944 – against the odds – survived the ‘Behar Massacre’. Most of his shipmates weren’t as fortunate, writes Lawrence Schaffler.

The brutality of Japan’s Imperial Army during WW2 is well-documented – less well-known perhaps is that her Imperial Navy could be equally barbaric. The Behar Massacre is one infamous example – where 69 prisoners from the British Merchant ship MV Behar were decapitated. All in the name of expedience.

Even though the atrocity was investigated in a war crimes trial after the war (and later covered in a few books), accurate information about the number, identity and eventual fate of the ship’s crew/passengers remains elusive. Inexplicably, for all its awfulness, the Behar Massacre remains little more than an obscure footnote in WW2 maritime history. Dora’s plaque is a small consolation for the victims’ relatives.

The story goes something like this.

Displacing 7,489 tonnes the MV Behar was one of a fleet of merchant ships owned by London’s Hain Steamship Company Ltd. Launched in mid-1943 at the Barclay Curle’s shipyard on the Clyde, her career would be tragically brief.

She left Melbourne in February 1944 bound for the UK (via India) carrying 796 tons of zinc and around (the tally varies) 108 crew and passengers – a mix of British, New Zealand, Indian, Chinese and Goanese men, as well as two women. Among them was Dora’s father – Captain Green. He was a passenger on this voyage, heading back to work (after three months leave) with the Indo-China Steam Navigation Company. Captain Maurice Symons was the skipper.

On March 9, somewhere south-west of the Cocos Islands the Behar was spotted by the 12,000-tonne Japanese heavy cruiser Tone. The warship’s gunners pumped countless shells into the freighter which quickly sank. Three of her crew died in the barrage – the rest clambered into four lifeboats and were taken aboard the Tone. And then things got even nastier.

Everyone was stripped of most of their clothing, their arms tied behind their backs, lashed to nooses around their necks. They sat on deck in the baking sun for several hours, before being taken down below. More severe beatings followed, and they spent the next six days in dark, poorly ventilated compartments.

The Tone’s skipper – Captain Haruo Mayuzumi – had in the meantime informed his superior officer, Vice-Admiral Naomasa Sakonju (aboard the flagship Aoba) about the sinking of the Behar and the 105 prisoners. The news didn’t sit well with Sakonju.

Naval orders stipulated that all enemy ships were to be captured (presumably to supplement the Imperial Navy’s rapidly dwindling fleet) – not destroyed. But he was particularly incensed because Mayuzumi had ignored another standing order: only a few selected prisoners were to be kept for interrogation. What should he do with the others? asked Mayuzumi. “Dispose of them” was the curt response.

Flirting with a court martial and perhaps his own ‘disposal’, Mayuzumi chose to ignore that instruction and instead took his ship and the prisoners to the Javanese port of Tandjong Priok. Newly irritated by this transgression, Sakonju stipulated that 36 (again, the number varies) would become POWs – the remaining prisoners were to be taken out to sea and executed.

It seems this directive jarred with Mayuzumi’s Christian values, but orders were orders – so he took the Tone out to sea. On the night 18/19 March, the 69 prisoners were assaulted, and one-by-one forced to their knees and beheaded.

Dora’s father – along with the Behar’s skipper, some senior officers and the two female passengers – was one of the ‘lucky’ 36. After interrogation everyone was interned in POW camps, but with two others Captain Green was sent to work as a slave labourer on a coal mine in Japan, enduring repeated physical assaults.

The trial

A few years after the war ended a British Military Court in Hong Kong investigated the Behar Massacre (September 1947). Dora’s father was one of the witnesses. Sakonju was sentenced to death. Mayuzumi got seven years in prison.

And what happened to Dora’s father? He met a Scottish nurse working in Hong Kong. They married and decided to settle in New Zealand. He operated a fishing charter business in the Bay of Islands with a vessel called the Ayr – and also skippered a dredge. He died in 1963 (aged 63), when Dora was 10 years old.

Like many war vets, he never spoke about his experience at the hands of his captors – not entirely surprising given the horror of the Behar Massacre.

As the plaque says – may the victims rest in peace.

Further reading

Much more information about the massacre can be found in the following books, but obtaining copies isn’t easy: The Behar Massacre, by David Sibley (published 1997), Blood and Bushido: Japanese Atrocities at Sea by Bernard Edwards (1991) and Betrayal in High Places by James Mackay (1996). The following link, to an article by Paul Weaver, also provides information: https://web.archive.org/web/20091013072342/http:/www.aamh.asn.au/news/0080.pdf

AUCKLAND INTERNATIONAL SAILING CENTRE

Established nearly 120 years ago in Auckland, the Seafarers Centre remains a welcome facility for merchant sailors visiting the city. In the days before containers, ships spent quite a while in port unloading/loading cargo. The Centre was a place to relax – a welcome change of scenery.

Today, Chris Barradale – himself a Maritime Master – is the chairman of the Centre, and says it still operates as a facility for visiting sailors who typically drop in for a cup of tea or a game of pool, or to use its internet facilities.

Unveiling a plaque to the victims of the Behar Massacre, he says, is appropriate for the Centre. “It now hangs among many similar plaques commemorating Merchant sailors, and if we didn’t acknowledge their lives and bravery in this way, they would all be forgotten – becoming just another statistic of maritime history.”

Auckland’s Seafarers Centre is one of 260 located in ports all over the world, operating 24/7 in 71 countries.