The widespread acceptance of electric vehicles (EVs) has undoubtedly helped stimulate interest in electric-powered vessels (EPVs), writes John Macfarlane.

Not before time – on litres of fuel burned per 100km, boats powered by international combustion engines (ICE) can be some of the most inefficient fuel users on the planet; see chart below. However, as we will see, while EPV technology has made giant strides lately in vehicles, it still has a long way to go before it can match the power-to-weight ratio of an ICE for boating.

Despite this, EPV can be an excellent option for specific, targeted applications, and the technology, systems and equipment for those applications are proven and readily available. The chart opposite looks at EPV’s pros and cons.

Looking closer at the limitations of electrically powered boats, the four significant ones are range, space/weight, speed, and capital cost.

Range – extremes aside, practically, most EPVs offer somewhere between four to 10 hours of usage between charges.

Space/weight – the inherent difficulty, yet to be genuinely overcome, is the space needed and weight of the batteries required to hold a specific amount of energy, both of which are considerably higher than for the equivalent amount of fossil fuel energy.

Speed – monohulls generally require a high power-to-weight ratio engine to achieve planing speeds. The weight of the necessary batteries makes it virtually impossible for a monohull to achieve more than displacement speeds using electrical power. However, multihulls, subject to different hydrodynamic rules, especially those fitted with foils, can be driven to more than displacement speeds by electric power.

Capital cost – the cost of an EPV motor and its batteries is considerably higher than the cost of an equivalent ICE powerplant. Unlike an ICE powerplant, ever-newer technology makes EPV subject to high depreciation rates, which are worsened by the relatively short lifespan of today’s batteries.

Potential buyers of an EPV (or buyers contemplating replacing an ICE powerplant with electric) must establish upfront if one or more of the four limitations listed is a deal-breaker. If that’s the case, an ICE powerplant will likely be more practical, less expensive to buy and subject to considerably less depreciation.

Batteries

Batteries are integral to an EPV and are a huge subject in their own right. Unquestionably, batteries remain EPV’s Achilles heel, and the perfect battery remains a dream.

Lithium-ion Phosphate batteries provide the best power-to-weight storage ratio of the currently available battery types. EPVs require sizeable battery banks, typically 48V, with more batteries equalling more range.

The primary downside of Lithium-ion Phosphate batteries is their price. Also, no battery lasts forever. A quality Lithium-ion Phosphate battery, correctly installed and well maintained, has an expected lifespan of between 3,000 and 5,000 partial cycles (the number of charging and discharging cycles).

Charging

Charging a bank of five, 10, or 20 48V Lithium-ion Phosphate batteries with 240V shore power is easy enough for EPVs returning to a marina each night. The difficulty is charging EPVs’ batteries when cruising further afield.

Onboard solar and wind charging are obvious options; however, they take time. A day motoring an EPV will likely require at least another sunny and/or windy day to recharge. This will require a careful eye on the weather to avoid getting caught in a poor anchorage. Of course, one could use an ICE to drive a generator to charge the batteries, but then it’s back to burning fossil fuels.

Yet another option is a parallel hybrid system, which uses an ICE for propulsion and an electric motor/generator (see more below) for low-speed propulsion and charging, respectively. This allows the batteries to be charged faster than solar or wind.

Ideal applications

Even given the range, speed, space/weight and capital limitations previously discussed, an EPV can still be viable, especially if noise, pollution or fossil fuel emissions are considered important factors.

Some examples of ideal EPV applications

Tenders – electric outboards for tenders are light, quiet, easy to use, and have no smell. Their range is the main shortfall – depending on the model, at full power, an electric outboard will give somewhere between 45 minutes to just over an hour before requiring recharging. Slower speeds will make the charge last longer. However, recharging can take up to 18 hours.

Daily hire boats – speeds and range are usually low, the boats are big enough to carry sufficient battery storage for a full day, and overnight charging is easy. Additionally, capital costs are amortised relatively quickly because these boats are often in constant operation. Additional bonuses include low running and maintenance costs, low noise, no smell, and easy operation by the hirer.

Sheltered water harbour ferries and canal boats – fall into a similar category and are another potential growth area.

Daysailers and harbour racing yachts – especially those on marinas with ready access to shore power for charging. Range is not usually an issue, so the number of batteries can be minimised.

Multihulls – catamarans especially have unlimited potential as EPVs. Their slim hulls are not subject to the same resistance curves as monohulls, meaning they can be driven to higher speeds without massive horsepower.

Additionally, their large deck areas can accommodate solar panels, also into the structure, without aesthetic or windage penalties. Adding foils to multihulls is another potential game changer and already a reality.

Cruising boats – replacing an ICE with 100% electric power. The main issue with this option are the limitations of onboard charging when away from 240V mains charging facilities. There will likely be occasions when onboard charging is found wanting.

Parallel hybrid system – standard ICE propulsion and a combined electric motor/generator unit. The ICE is used when higher speeds and range are required, switching to electric for low speeds, low wake and/or short runs. Because the ICE allows independent charging, range is not an issue, so battery storage can be minimised, saving weight, space, and cost. Capital costs will be higher than for an ICE-powered boat but less than for a pure EPV setup.

Summary

As things stand today, while EPV can be an excellent choice for specific, targeted applications, it has significant limitations and roadblocks once outside specific parameters of speed, space/weight, range, and capital cost. An ICE still rules supreme on the water for nearly all general-purpose boating, especially when range and speed are required.

This situation will likely persist as long as fuel remains around its current price. Those who experienced the 1970s fuel shocks will remember when high-powered launches and V8 cars were overnight persona non grata and trailer yachts became hot. It’s easy to visualise that happening again, and when the masses suddenly decide that ICE boating is unaffordable, watch for an explosion in the popularity of EPVs.

While we’re waiting for new technology to improve EPVs’ range, battery space/weight, speed and capital costs, the easiest way boaties can minimise their fossil fuel usage is to maximise the fuel efficiency of their current boat. Driving your boat at its most fuel-efficient speeds, keeping the bottom clean, ensuring the propeller(s) are true and correct, and servicing the engine(s) regularly can all help save significant amounts of fuel.

Think globally, act locally.

EPV PROS & CONS

- Lower noise, typically, the loudest noise is from the drivetrain

- Low revs and high torque; reduction gears are generally not required

- No exhaust smell

- Air-cooled; one less skin-fitting

- No polluting fossil fuel emissions when operating

- Low running costs, apart from the cost of charging

- No fossil fuel is used during operations

- Lower maintenance costs

- Lower range; limited by battery storage and/or recharging time

- Limited to displacement speeds; extremes and foils excepted

- Battery space and weight

- High capital costs, especially batteries

- Higher emissions incurred during manufacturing, especially batteries

- High-tech battery recycling is problematical

Examples of Successful EVP Applications

Founded in 2014 in Denmark, GoBoats are self-drive electric open boats. They are built in Denmark using recycled plastic and driven by a German electric outboard motor. Licenced for eight people, the boats are speed-limited and create virtually no wake. The concept has proved extremely popular, and there are now licenced fleets of GoBoats in Europe, England, and Australia.

The rubber-mounted Smartline 5kW electric motor fits easily into the space once occupied by the Bukh and utilises the old engine beds. Electrical power is supplied by 13 Discover LiFePO4 48V Lithium-ion Phosphate batteries, producing 390Ah at 48 volts. This gives up to 10 hours of motoring at 5.5 to 6 knots – more than acceptable for a cruising yacht for the inner Hauraki Gulf. The batteries occupy all the space in Santa Cruz’s aft quarter berths, and with hindsight, reducing the number of batteries would have been possible (see photos on previous page and page opposite).

The ability to use 240V shore charging has been incorporated and controlled by the Discover batteries’ internal management system. The Victron management system gives complete touchscreen control, with a colour display showing battery charge, charging rates, temperatures, and both automatic and manual operation of the cooling fans.

Onboard charging is provided by 900W of solar panels installed on a stainless-steel arch over the cockpit. On a sunny day, these panels produce up to 20 amps DC at 48V.

One paradox of an electric installation is that because the motor is so quiet, driveline noise, usually masked by the diesel’s sound, can become obtrusive. Blue Water Electrical and its allied company, Auckland Marine Systems, have done an outstanding job with motor-to-driveline alignment, propeller shaft bearings, and propeller to minimise noise and vibration. Under power, Santa Cruz is uncannily quiet, and the simple hand control makes going from ahead to astern instant and effortless.

Santa Cruz retains a standard 12V lead-acid house battery for lights, radios, and other onboard systems, charged by a separate solar panel on the cabin top.

While overall performance and range are excellent, the capital costs were very high. This was partly due to post-COVID cost increases and extra labour required to address other issues discovered during the repower. While their H28 is certainly over-capitalised, the Talbots are more than happy with the outcome, which is the litmus test.

Lithium makes sense

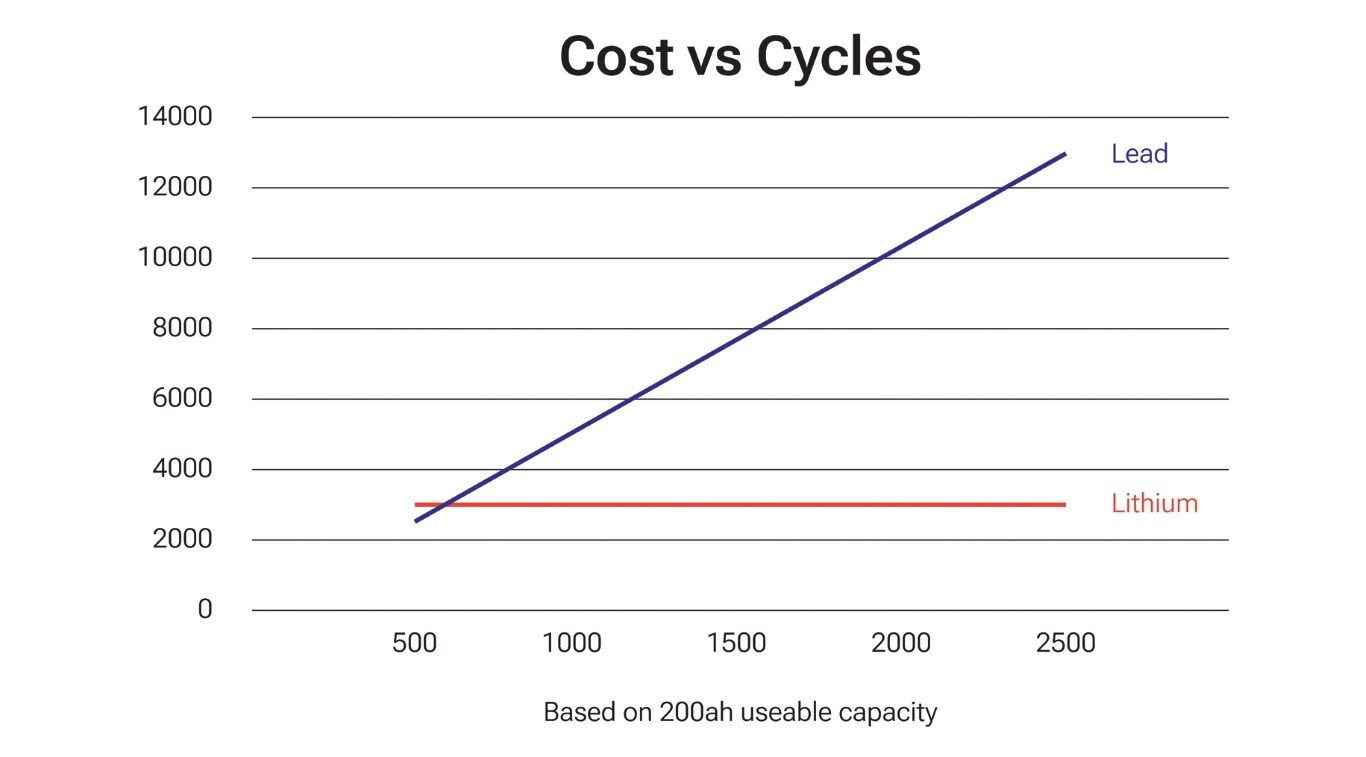

Victron Energy’s Smart Lithium offers groundbreaking form factor in capacity-per-square inch of footprint, meaning not only weight saving, but space saving too. The round-trip energy efficiency (discharge from 100 % to 0 % and back to 100 % charged) of an average lead-acid battery is 50-80% compared to the 92% of lithium batteries.

Lead-acid battery performance deteriorates greatly over time. By the time you need to replace a Victron Smart Energy battery, you are likely to already be on your fourth or fifth set of lead-acid batteries. In addition, Lithium will deliver close to its performance at installation throughout its more than 10-year life.

Lithium battery benefits include higher energy outputs onboard to keep up with your lifestyle and the ability to power your vessel without needing a generator – even with induction cook tops, ovens, and a coffee machine onboard.

The ability to run a ‘quiet ship’ and the reduction in fuel costs through not running a genset result in a more enjoyable time on the water.

“We have been overwhelmed with conversations at the recent boat show with people regretting not switching to Lithium in recent system installations or upgrades. The current price would drive this decision over the line, and add to that the benefits of Lithium, and it seems to be a no-brainer for many,” says Chris Bowler, the Electrical Product Manager for Lusty & Blundell.

The team at Lusty & Blundell is the only Victron Energy-approved service centre in New Zealand with projects ranging from new installations, retrofits and upgrades. It fully supports its network of installers across the country.

Small vessel systems including a smart BMS, Shunt and Smart Lithium Battery start from only $3,099.