The Arab sail and dhow

During the Islamic Golden Age (8th to 13th centuries), Arab sailors perfected the use of the lateen sail and rig on their dhows – slender, elegant vessels used extensively across the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea. The triangular lateen sail could pivot and catch the wind from the side, creating a pressure differential that generated forward momentum, allowing the ship to sail at an angle into the wind.

With its unique set-up, the dhow could out-sail the square-rigged craft of the Mediterranean and better navigate contrary winds, making dhows ideal for monsoon-driven trade routes connecting Africa, the Middle East, India, and Southeast Asia.

Adapting their boats further with the stern-mounted rudder of the Chinese junks, Arab mariners also made significant contributions to nautical navigation, using astrolabes, compasses, and detailed nautical charts. All these marine innovations helped support the growth of Islamic maritime trade networks, as well as further popularising the ongoing use of the lateen (and settee-style) sail and rig.

The Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery, spanning the 15th to the 17th centuries, was an era of unprecedented global exploration that was fundamentally enabled by a major revolution in both maritime technology and sail design. These advancements transformed ships from vessels dependent on favourable winds, into versatile, ocean-crossing behemoths capable of navigating the globe’s unpredictable wind patterns. The synthesis of two distinct sail types was the key that unlocked this new age of exploration.

The main innovation was combining both the square sail and the lateen sail on a single large ship. The square sail (a large, rectangular piece of canvas hung from a horizontal yardarm) was remarkably efficient for sailing with the wind at its back, acting as a broad, powerful scoop that captured the full force of a following breeze. This made it ideal for long, direct voyages, but its rigid design meant it was almost useless for sailing against the wind or for manoeuvring in tight spaces. A ship with only square sails was completely at the mercy of the prevailing currents and winds, making return voyages to Europe from Africa or the Americas a difficult feat.

However, combining this with the lateen sail spawned the breakthrough to develop truly global seafaring vessels. This hybrid rig enabled ships to harness both downwind and crosswind forces, allowing navigators like Vasco da Gama, Christopher Columbus, and Ferdinand Magellan to travel vast distances with greater confidence and control.

The Portuguese caravel, a vessel that famously harnessed this design, was highly manoeuvrable and could navigate tricky coastal waters and sail against headwinds, making it the perfect ship for the initial exploratory voyages along the African coastline.

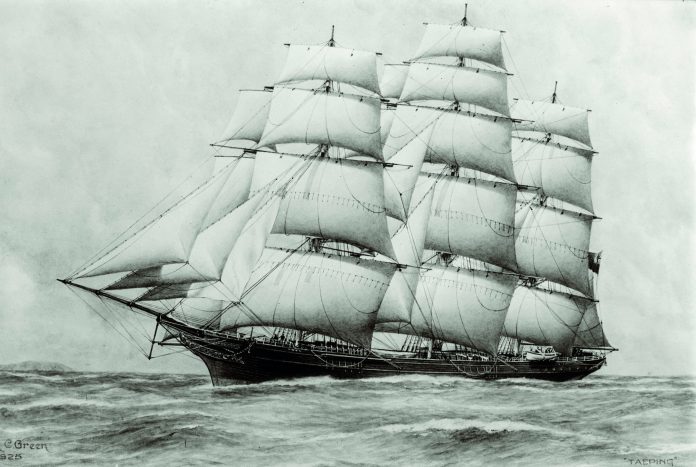

Combining the strengths of both sails led to the development of totally new boat designs – firstly the carrack and, later the galleon. These multi-masted vessels featured a combination of square sails on the foremast and mainmast for downwind speed and power, along with one or two lateen sails on the mizzenmast (the rearmost mast). This versatile rigging allowed ships to maintain high speeds on long ocean voyages while also providing the manoeuvrability needed to navigate unfamiliar harbours and coastal currents. It gave sailors the ability to return to port regardless of the direction of the wind, fundamentally changing the economics and practicality of long-distance exploration. This technological union was the single greatest factor that enabled the Age of Discovery to live up to its name, allowing

a handful of nations to map, connect (and then colonise) the world.

Sailcloth materials also improved significantly during this era. Canvas made from hemp or flax became the preferred fabric, replacing earlier linen and cotton varieties for its durability and wind resistance.